#5 The Mother of All Battles, part 3

Scud Slinging

At the end of history, there are no serious ideological competitors left to liberal democracy.

Francis Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man (1992)1

i

Late January 1991. In all likelihood many in the 24,000-strong Marine decoy force were watching the war unfold on CNN while they idled away their hours on board their ships.2 What purpose did the top brass have in mind, keeping these men afloat in those warm Gulf waters? That of making Saddam Hussein believe an amphibious assault was in the offing, and thus forcing him to commit a substantial portion of his forces (this turned out to be between 60,000 and 80,000 men) to the defence of the Kuwaiti shoreline, weakening his defensive line along the border with Saudi Arabia, where the actual Coalition ground offensive was to take place. But Saddam clearly felt this was not enough to protect his coastal flank, so he took further steps.

Toward the end of January massive amounts of Kuwaiti oil began to spill into the Persian Gulf, the result of a deliberate act of sabotage on the part of the occupying Iraqi army, one that may have been intended to prevent that much-feared amphibious assault. Each day for a week, Kuwait’s Sea Island Oil Terminal spilled between 70,000 and 80,000 tons of crude into the sea.3 As a defensive measure it likely wouldn’t have been enough, if push came to shove, to hold the Marines at bay. But maybe that wasn’t ‘the madman of the Middle East’s’ primary aim anyway? With this act of gross ecological vandalism Saddam seemed to be expressing his snearing contempt for his enemies. Not only was it a symbolic slaying of the new Western sacred cow, the environment4, it also drew specific attention to the oil, that black gold—as if to say, We all know why you’re really here. Throughout the war there was a marked contrast between Saddam Hussein’s contemptuous, sarcastic, and largely ineffective (in purely military terms) actions and the dispassionate, clinical and war-winning rationalism of the Coalition. This contrast contributed to the Gulf War being perceived as a simple struggle between good and evil, which is certainly how I saw it as a naïve 14-year-old entranced by the stealth fighters and smart bombs, the cruise missiles and night-vision cameras. And of course it was exactly the view of the conflict the US and its allies wanted the world to have.

A few weeks after the sabotaging of the oil terminal Saddam ordered his men to set the Kuwaiti oil wells alight, as if to drive home that point about what the Coalition had really gone to war over. In early February US satellites detected the first black smoke plumes; after two weeks so many wells were burning that the plumes had become vast, drifting over hundreds of square kilometres of desert. As with the deliberate oil spill, this sabotage was likely carried out for military as well as for symbolic purposes: the thick smoke could screen the now-retreating Iraqi army, hindering the use of laser-guided missiles and bombs and frustrating efforts to observe the battlefield with spy satellites.

ii

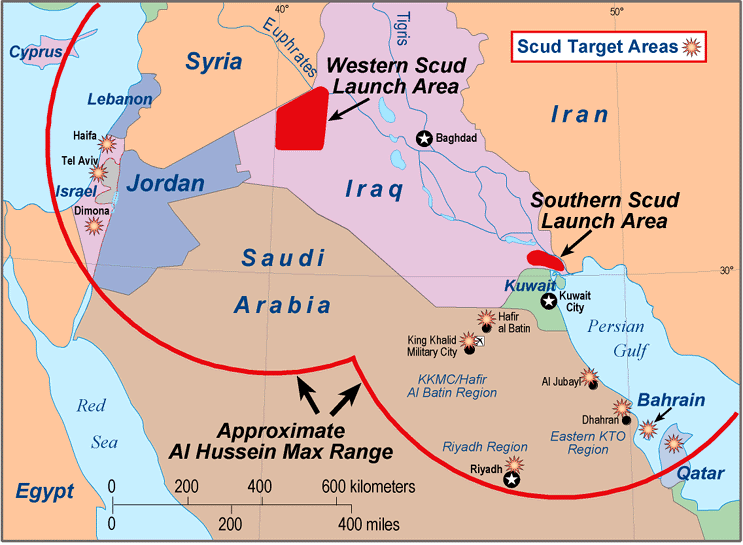

By my reckoning there was one more significant Iraqi response to the massive Coalition assault, this third being the Scud campaign. This campaign is especially interesting because it’s here that Saddam came closest to splitting the Coalition and causing some real geopolitical havoc—much closer than most people realise. And for me, the Scud is a most fitting weapon for the real-time era: even if radar detects it mid-flight, it’s still upon you almost before you know it. There is very little, if any time to decide how to respond, just like events in our hectic era.

At the time of the August 1990 invasion of Kuwait, Scud Brigade 224 was already deployed in the western Iraqi desert, within striking range of Israel5. Besides mobile launchers there were also fixed Scud launch sites at airbases in this desert area. In September the new Brigade 223 was activated; it was partially equipped with only four mobile launchers of a new, simpler type, the Al-Nida.

The Iraqis had at their disposal both ‘vanilla’ Scud Bs and a longer-range Scud variant, the Al-Hussein. This latter had been developed by Saddam’s men during the long war with Iran, after the Soviets refused to supply them with their longer-range ballistic missile, the TR-1 TEMP. Once operational, the Al-Hussein had allowed the Iraqis to carry out missile strikes on the Iranian capital, plus Qom and Isfahan, all beyond the range of the Scud B6.

Although the Iraqis had managed to achieve, with their modified missile, more than double the Scud B’s range (from 300 km to 650 km), they couldn’t improve upon the original weapon’s woeful accuracy.

The origins of the Scud recall Thomas Pynchon: in the aftermath of WW2 the Soviets dispatched teams of specialists to acquire advanced German technology. Amongst other booty they returned with German V-2s, and it was by copying that rocket that the USSR built, in 1948, its first ballistic missile, the R-1 (Raketa-1). It wasn’t a hit with military commanders: too expensive, too inaccurate, too unreliable—the V-2 clones crashed about half of the time.

A series of somewhat better missiles led, in the early 50s, to the R-11 Zemlya, or Scud A, the first ballistic missile to which NATO assigned the Scud codename. The R-11’s accuracy wasn’t a tremendous improvement over earlier models’, yet it didn’t need to be. The missile’s role was to deliver a nuclear warhead, one of relatively low yield: around 50 kilotons, equivalent to a little over 3 Hiroshima “Little Boy” bombs. In the event of war with the West, Scud tactical nukes, carried on trucks and raised into position by vehicles called erectors, would be launched by Soviet units in forward areas. Since as ballistic missiles plummet to earth they travel faster than the speed of sound, the first—and probably last—an American GI, British squaddie or west European city dweller would know of an attack would be a burst of blinding light abruptly flooding the landscape.

In the early 70s Egypt approached the USSR with an offer to buy a later model, the R-17 / Scud B, as a conventional weapon system—ie the missiles would be fitted with high explosive warheads instead of nuclear ones. The Soviets accepted, and a shipment of Scud Bs and TELs (Transportor-Erector Launchers) arrived in Egypt just in time to be used in a very limited capacity in the Yom Kippur War of 1973.

Iraq was another early adopter, receiving its first Scud Bs in 1975. For Arab states Scuds served as a symbolic counter to the Israelis’ Jericho missile, and offered a way to attack the Jewish state that didn’t rely on aircraft. Other recipients of the Scud B included Libya, Syria, Iran (by way of Libya and North Korea), Afghanistan and Yemen. Despite the Scud B’s dubious military effectiveness in the non-nuclear role, the region’s Muslim leaders seem to have found it pretty appealing, this idea of a volley of the missiles plunging down from the heavens without warning, like a judgment of Allah. And, as Saddam Hussein no doubt realised in 1975, ballistic missiles could wreak political havoc out of all proportion to their very modest military value.

iii

Let’s return to 1990.

The Scud was identified as a significant threat by the Coalition early on, for two reasons:

Firstly, it might be used to deliver chemical7 and biological8 weapons. The Iraqis had used weaponised chemical agents multiple times during the 1980s—on Iranian troops during some of the more desperate fighting of the long war with Tehran, and, later, on Kurdish Iraqi citizens in a ruthless campaign of ethnic cleansing.

Secondly, and relatedly, the Scuds Saddam would almost certainly launch at Israel might succeed in bringing the Jewish state into the war—an event that would be highly likely to split the Coalition and precipitate a major crisis.

To prepare for the first eventuality, the US and its allies issued their forces with NBC (Nuclear, Biological, Chemical) suits and had them take a cocktail of vaccines and anti-nerve agent pills. Although it seems every one of the vaccines and drugs had previously been approved for use, the effect of combining them all was not known. Once again Western soldiers served as guinea pigs, just as they had during the early days of atomic weapons testing.

The second concern led the US to send MIM-104 Patriot missile batteries to Israel, in addition to the ones it deployed in Saudi Arabia. The Israelis did in fact possess their own Patriots, but these were in the preliminary stages of deployment. The MIM-104 was a surface-to-air missile designed to bring down aircraft—it hadn’t been designed as an anti-ballistic missile but it was the best thing available. The US had signed the ABM Treaty with the USSR in 1972, in order to maintain the nuclear balance of terror that had thus far prevented another world war. It would remain in effect until 2002. As a result, ABM technology was not at an advanced stage in 1991. The Iron Dome system was still decades away.

The great concern of the Israeli government was that Saddam would attack their cities with chemical weapons, either by fitting Scuds with warheads containing mustard gas or nerve agent (although this was believed to be beyond Iraq’s capabilities in January 1991, Saddam’s men were assumed to be working on it), or by sending in bombers to deliver the toxins (a known Iraqi capability). Israel therefore issued its citizens with gas masks in the closing months of 19909.

The Scud bombardment—of Israeli cities and of Coalition facilities in Saudi Arabia—began in the early hours of January 18th. Crews manning Patriot launchers in both countries were tasked with shooting down the incoming rockets. Given the limitations of the Patriot system at that time (its ABM capabilities were greatly improved over the subsequent decades), intercepting Saddam’s missiles was never going to be easy. Although the Al-Hussein had design flaws, ironically these made defending against it more complicated and difficult—the modified Scud tended to break up into multiple pieces on its descent, requiring the use of multiple Patriots, one for each of the large pieces of debris, one of which would contain the warhead. However, the media covered up the MIM-104’s ineffectiveness, firstly out of a concern to prevent panic among Israeli civilians. Secondly not to give moral support to the Iraqis. And thirdly simply out of pride, the almost unlimited capabilities of Western technology being one of the key ‘themes’ of the war, a notion almost everyone in the West became invested in.

The Coalition used A-10 Warthogs to hunt Scud TELs by day. By night F-15s equipped with LANTIRN (Low Altitude Navigation and Targeting Infrared for Night) pods were employed. Yet regardless of the time of day, locating, let alone destroying the Scud launchers proved remarkably difficult. Scud crews employed ‘shoot and scoot’ tactics, hiding their vehicles in wadis and culverts and beneath bridges immediately after sending a missile on its way.

Readers of Alan Partridge’s favourite book, ‘Andy McNab’s’ Bravo Two Zero, will know the Coalition dropped special forces teams into the western Iraqi desert to tackle the elusive Scud menace. McNab’s SAS unit was tasked with cutting the underground communications cables that ensured Scud Brigade 224 remained in touch with central command in Baghdad.

It seems the special forces teams had some success disrupting the Scud units’ supply lines. Where they did less well was in their efforts to attrit the Scud brigades. The commandos were tasked with liasing with the strike teams of A-10s and F-15s in order to vector them in to fire on Scud TELs. This proved exceptionally diffcult, and by the war’s end Coalition air forces had failed to hit a single TEL, even after 1,500 sorties.

Tensions were running extremely high in Israel throughout the bombardment. On more than one occasion Tel Aviv determined to send special forces into Iraq to do the job the Coalition seemingly couldn’t: neutralise the Scud menace. But on each occasion US Defense Secretary Dick Cheney, who was in almost daily contract with the Israelis via a special hot line, managed to dissuade them. Everyone knew the entry of Israel into the war might split the Coalition, with grave consequences. Of course that was precisely what Saddam was hoping to precipitate with his Scud attacks.

The deadliest Scud strike of the war occurred, not in Israel, but in Saudi Arabia. The US military barracks at Dhahran was struck on February 25th, at 8.30pm. 28 soldiers were killed and another 110 injured. Most of the casualties were reservists from Pennsylvania10. It was the single biggest loss of life suffered by the US military during the war. A Patriot battery had tracked the incoming missile; the failure to intercept was down to a shift in the range gate of the radar, a consequence of the software having been used continuously for more than 100 hours without resetting.

By the war’s end on February 28th, the Scud campaign had claimed fewer Israeli lives than Saddam had likely hoped for. Although 39 missiles had been fired at Israel, only 6 of them had landed in populated areas. 2 people had died as a direct result of the strikes. There had been between 11 and 74 fatalities from incidental causes: heart attacks, incorrect use of gas masks, and incorrect use of atropine, which was an anti-chemical weapons drug11. Over 200 people had been wounded. Had the casualties been higher, Saddam might’ve got what he wanted: Israel entering the war, the only thing that could realistically throw the Coalition’s plans into disarray.

In the event, the chemical and biological attacks so feared by the Coalition and the Israelis did not occur, at least officially. Presumably Saddam came to the conclusion that employing WMDs would just be too risky, might well lead to Coalition tanks in Baghdad. By sticking to conventional weapons he would likely lose the war, but his regime could survive.

Nevertheless, in the war’s aftermath many Coalition troops were confirmed to have been exposed to low, non-lethal levels of mustard gas and nerve agents, these chemicals probably having been released when facilities housing them were hit by air or artillery strikes.

The role of these factors—both the Iraqi chemical weapons and the Coalition’s countermeasures against them—in the pathology of the mysterious illness known as Gulf War syndrome, remains controversial, neither confirmed nor disconfirmed12.

iv

For the attitude of modernity, the high value of the present is indissociable from a desperate eagerness to imagine it, to imagine it otherwise than it is, and to transform it not by destroying it but by grasping it in what it is. Baudelairean modernity is an exercise in which extreme attention to what is real is confronted with the practice of a liberty that simultaneously respects this reality and violates it.

Michel Foucault, What Is Enlightenment? (1984)13

From 1990 to 2003 sanctions were imposed on Iraq. It goes without saying that while these sanctions degraded quality of life in the country, they failed to remove Saddam from power. It’s difficult to establish just what the impact of the sanctions was on ordinary Iraqis—statistics on excess deaths were put together by UNICEF in the 90s, with a figure of 500,000 child deaths given, but a suspicion of fraud hangs over the data14. Whatever the case, the suffering of ordinary Iraqis under the sanctions regime was largely ignored in the West. Those who did give it any thought found it easy to blame Saddam for not having the good grace to remove himself from power.

Over 30 years after the Gulf War and almost 16 years after his execution, Saddam Hussein remains an enduringly popular figure in parts of the Middle East. In Jordan, in particular, there has been a thriving Saddam cult for decades, with the Iraqi president’s likeness on display in countless places in the capital Amman15. Perhaps we can infer from this that the likelihood of the region’s peoples embracing Western liberalism and democracy has never been very high.

As I wrote in part 2 of this series, the victorious outcome of the Gulf War fed into the triumphalist End of History mood that dominated the 1990s in the West. Largely thanks to the highly distorted image of the war presented by the media in collaboration with the White House and the Pentagon, the fiction of the Gulf conflict as largely bloodless was born. It was a flattering myth people readily believed, suggesting that that passion for reality that Baudelaire identified as a key feature of modernity was on the wane. Fading, too, was the equally vital passion for liberty—allowing oneself to be lied to by the powers that be for the sake of one’s peace of mind is an example of voluntary servitude. This is why I say modernity proper was already on its way out in the late 20th century. Modernity as passion degenerating into modernity as duty (and that’s a possible definition of postmodernity). A feature of this entropic trend was a fading of vision that allowed the End of History hubris to establish itself. After 9/11, a shocked and wounded but still overconfident America flung itself into two imperial adventures. The consequences of those I will leave for another post.

It’s interesting that the ‘grammar’ of CNN’s war reporting proved highly influential. The roving, sometimes shaky camera of live reportage became a widely recognised signifier of, not so much reality, but rather of contemporaneity. A signifier of being up to the minute, of ‘the now’. The shaky camera carried the implication of an unstable & uncertain reality, and conveyed a sense of urgency, at times of panic. The most striking thing about the hit TV series NYPD Blue was its prominent use of the shaky camera.

It’s notable that perhaps the most famous account of derring-do to emerge from the war, Andy McNab’s Bravo Two Zero, was largely fictional. The real Desert Storm provided an early taste of the increasingly inhuman world of the century to come. Entirely plotted out on graphs & spreadsheets long before the first missile was launched and bomb dropped, it was a military campaign in which spontaneous human passion did not figure because there was neither need nor room for it. Aircraft like the F-117 Nighthawk were the true face of the war, and of the disturbing world to come: ultra-high-tech, alien, inhuman.16

Yet Westerners turned away from this unsettling reality, preferring instead to dwell in a cosy humanist delusion, a false belief Fukuyama’s 1992 book set the seal upon17. These were the early stages of a dramatic bifurcation between the world as it is and the world as we represent it to ourselves.

Fukuyama, Francis, The End of History and the Last Man, Free Press 1992.

Wikipedia, Gulf War oil spill.

It seems reasonable to suppose the first photos of the Earth taken from space in the 1960s helped drive the new environmentalism. A new ‘world picture’ (to use Heidegger’s term) was minted, and the unfamiliar notion of human beings as the inhabitants of a fragile planet entered the discourse.

Zaloga, Steven J, Scud Ballistic Missile and Launch Systems 1955—2005, Osprey Publishing 2006.

Karsh, Efram, Essential Histories The Iran—Iraq War 1980—1988, Osprey Publishing 2002.

Wikipedia, Iraqi chemical weapons program.

Wikipedia, Iraqi biological weapons program.

The Jerusalem Post, 27 years since the Gulf War - why didn’t Israel respond?, February 12, 2008.

Penn Live, ‘There were people laying everywhere’: The Iraqi Scud missile attack that killed 13 Pa. soldiers 30 years ago, February 25th, 2021.

Wikipedia, Iraqi rocket attacks on Israel.

Gulf War syndrome, which affected and continues to affect large numbers of veterans on both sides, remains one of the darkest legacies of the conflict. Depressingly, the UK government has spent over 30 years avoiding addressing the suffering of British veterans affected by GWS—the Royal British Legion continues to campaign for a decent response from the Ministry of Defence.

This text is collected in Foucault, Michel, The Foucault Reader, Pantheon Books, 1984.

Atlas Obscura, The Country That Still Considers Saddam Hussein A Hero, October 14th, 2020.

The F-117 has been officially retired since 2008—in truth it is semi-retired, with examples occasionally being spotted in flight.

In one sense Fukuyama was correct to say history was at an end: the late 80s and early 90s saw the fulfillment of American liberalism’s utopian promise. It wouldn’t get any better than that; it was the end of that history. However, since progress and telos are essential to this ideology, it had to go somewhere. Consequently, American liberalism began to destroy itself.