#34 The New Age Generation, part 2

Delving further into the mystic currents of the 24th century.

III

In part 1 of this essay, I argue that a strain of New Age thinking can be found running through the first two seasons of Star Trek: The Next Generation. I link this mystical tendency to the liberal zeitgeist of the Eighties. I offer a breakdown of the season one episode “Where No One Has Gone Before” to illustrate my argument.

Now of course, a single episode does not a show’s sensibility make. If “Where No One Has Gone Before” were the only evidence of a New Age outlook on TNG I would not have bothered to write this essay (though I might well have written a different one on TNG). The other episodes worth mentioning in this regard I’ll come to in a moment. For now I want to consider composer Ron Jones’s flamboyent, synth-heavy music. Now synths, of course, feature heavily in most New Age music—especially synths with a distinctly Eighties flavour. In fact it’s precisely that mood, that vibe, that the first few (very synthetic) notes of the TNG title sequence evoke. That whole sequence, as the reader probably knows, is an Eighties update on the Sixties series’ opening titles. “Its five-year mission…” and “Where no man has gone before” make way for “Its continuing mission…” and “Where no one has gone before”. I don’t know if composer Ron Jones created the synth intro—that instantly recognisable phrase which segues into an orchestral theme equally memorable. This latter, by the way, was originally written by Jerry Goldsmith for Star Trek: the Motion Picture. But whether or not Jones honed that opening melody, it does gesture towards the same imaginative universe evoked by his TNG background music.

For me both versions of that opening phrase—The Original Series’ and TNG’s—are suggestive of the vastness and the enigmatic quality of space. In both cases what is evoked is Mystery. Of course the mood differs slightly between them. With TOS there’s a distinctly retro, perhaps naïve quality. With TNG it’s very Eighties: New Age / vaporwave.

Later Trek series went for different effects. Perhaps, by the Nineties, Mystery was felt to be a little naïve. Whatever the case, the spin-off shows obviously needed to find their own identities. Deep Space Nine’s main theme evokes Majesty. Voyager’s, Grandeur. As for the Enterprise main theme, the less said about that the better. Except for the odd episode or two, I have not watched Star Trek: Discovery or other ‘NuTrek’ films or series.

Ron Jones’s compositions for The Next Generation are extraordinary. He wrote numerous scores for the first two seasons of the show, some more for season three, a mere handful for season four. At that point he was let go by executive producer Rick Berman1, head of the Trek franchise following the ailing Gene Roddenberry’s unofficial semi-retirement and later death. Berman found Jones’s music too conspicuous, too keen to be noticed. He expanded on his reasoning in a 2011 interview:

Why was Ron Jones, who’d been composing music for TNG, dismissed after Gene Roddenberry’s death?

Berman: On various sites, one of them being Wikipedia, I’ve read some pretty nasty things that Ron Jones has said about me, with a general perception that his music was too good and I was not interested in good music. That is insulting and also absurd. The music on Star Trek was something that was supervised by me and by Peter Lauritson. Peter had been involved in hiring and firing conductors from the first episode of Next Generation to the last episode of Enterprise. Ron came on at one point, I forget exactly when, and he did numerous episodes for us. We got along fine. And at one point, because there were other composers we’d try out and we’d use for anywhere from one to dozens of episodes, it got to a point where neither Peter nor I were pleased with Ron’s work. As I believe I said at the time to somebody, he was doing the kind of scoring that was calling attention to itself. That doesn’t mean, as some people have interpreted it, that I wanted dull, boring music. What it means is that the music is there to enhance the scene that is going. The scene is not there to enhance the music. And Ron’s stuff was getting big and somewhat flamboyant. It was a decision that Peter and I made that was just a simple moving on to other composers. I think Ron was a perfectly good composer. I didn’t think he was in the same ballpark as Dennis McCarthy or Jay Chattaway, who we used a good deal of the time. But we decided to move on and try other composers.

In my view this was a bad creative decision, one of the worst taken during the series’ seven-year run. Many fans share my opinion. Jones’s TNG work is so highly regarded it’s been released as a CD box set entitled The Ron Jones Project. The collection’s over seventeen hours of music demonstrate both the composer’s industriousness and his remarkable range. While he was still on the show Jones enjoyed a surprising degree of freedom. This quote comes from The m0vieblog’s page on the composer:

I had creative real estate. I think I got away with a huge amount – I can’t figure out why, I don’t know what it was about. But when they decided to get rid of me, they decided to really change the music and sit with the composers. I never saw Rick at a session once.

“Where No One Has Gone Before”, the thought-provoking season one episode I discussed at some length in part 1, was evocatively scored by Jones. His music does much to establish the episode’s dominant mood of exploration and mystery.

Another favourite of mine among Jones’s scores is the one for “We’ll Always Have Paris”. While the plotting is less than memorable, this season one episode is enlivened by the wistful accordion with which Jones conveys Picard’s mixed emotions. On the one hand, nostalgic affection for an old flame he runs into after twenty-two years. On the other, irritation at his own “self-indulgence” after he recreates “their” cafe on the holodeck. Jones’s Gallic melodies remind me strongly of similarly wistful music Nobuo Uematsu created for the Final Fantasy series of JRPGs. The slight corniness of the accordion on “We’ll Always Have Paris” well conveys the bittersweet quality of Picard’s nostalgia.

In the underrated season one episode “Skin of Evil”, Security Chief Tasha Yar dies a meaningless death at the hands of one of TNG’s weirdest antagonists, a malevolent, living oil slick. Denise Crosby had decided to leave the show. She felt she hadn’t been given enough to do, which is odd, as she features prominently in quite a few episodes in the first season. “Code of Honor” for instance. It’s interesting that the writers opted to give Yar an unheroic death. Was it a punishment for abandoning ship? Possibly. Whatever the case, the randomness, the arbitrary nature of Yar’s death makes it hit harder. As a result the episode is more thought-provoking than it might otherwise have been. “Skin of Evil” is for me reminiscent of some of the darker, more Lovecraftian episodes of The Original Series’ first season (eg “The Man Trap”), and it benefits from a menacing, horroresque score from Ron Jones.

The episode is also notable for featuring one of the most New Age scenes in the whole series. I refer to Yar’s holodeck funeral scene, which takes place on a very synthetic-looking hilltop. The prominence looks astroterfed, the breeze-blown tree unreal, the sky too blue. You half expect to see a pod of silver CGI dolphins swimming serenely across that holo-sky. There’s also something surreal and New Age about the posthumous message from hologram Tasha. “You’re here now watching this image of me because I have died,” says the Yar recording, as calm and unruffled as if delivering a no-hard-feelings resignation speech. “Where No One Has Gone Before”, with that scene in which Picard encountered his dead mother, seemed to argue for the existence of an afterlife. Yar’s closing remarks at her funeral (I realise how odd that sounds) provide an atheistic contrast to that:

Death is that state in which one exists only in the memory of others. Which is why it is not an end. No goodbyes. Just good memories. Hailing frequencies closed, sir.

The funeral scene thus combines New Age aesthetics with a rather godless message, making it very Roddenberryesque. It brings to mind the atheistic mysticism of Star Trek: The Motion Picture, an underappreciated slice of cinema and the one Trek movie that can really be said to be Roddenberry’s.

Gene Roddenberry is commonly viewed as an atheist—William Shatner refers to him as such in “Chaos On The Bridge”, the 2014 documentary on the creation of Star Trek: TNG and its tumultuous first two seasons—and a comment the Star Trek creator made on Christianity lends credence to this opinion:

How can I take seriously a God-image that requires that I prostrate myself every seven days and praise it? That sounds to me like a very insecure personality.

However, a quote from very late in his life, when he’d become close to fringe philosopher Charles Musès, muddies the water somewhat:

It's not true that I don't believe in God. I believe in a kind of God. It's just not other people's God. I reject religion. I accept the notion of God.

Both these quotes appear on Roddenberry’s Wikipedia page—along with Musè’s assertion that Roddenberry’s outlook was “a far cry from atheism”—in the section on Religious views.

There’s certainly a strain of mysticism running through Star Trek: The Motion Picture, the sole Trek film Roddenberry was heavily involved in (Paramount, less than wholly satisfied with the first picture, sidelined him for the sequels). It’s a slow and ponderous movie which is nevertheless quite thought-provoking. As Commander Decker and Spock explain late in the story, the film’s antagonist, the machine entity V’Ger, is unable to access “higher levels of being” because its thinking is restricted to pure logic. Like a great many people in the modern era, V’Ger is hemmed in by rationalism.

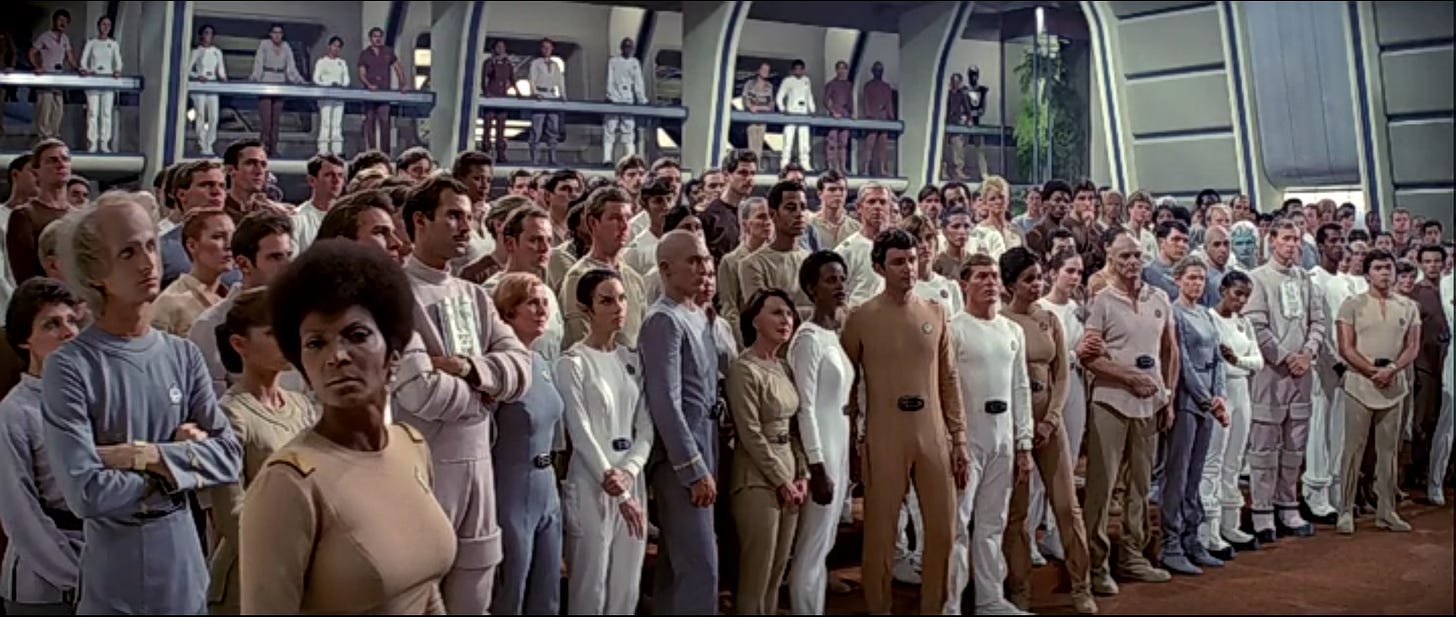

The Motion Picture gave Trek fans what is, by my reckoning, their first glimpse of Starfleet Headquarters in San Francisco. It strikes me as interesting that Roddenberry chose to locate his HQ, not in Washington DC or New York, but instead in the city that was the epicentre of the American counterculture throughout the Sixties and Seventies. Was he paying homage? Starting in the later Sixties, Roddenberry certainly played up his image as a radical progressive. It was a persona he’d invented for himself around that time by telling fans that Star Trek was a ‘Trojan Horse’ series—a way to smuggle controversial themes, and politics, onto network television. And network television, as Roddenberry had it, was highly conservative, resistent to the sort of radically progressive politics the Trek creator was (supposedly) committed to. Fans, especially female ones, eagerly embraced this notion of Star Trek as a courageous trailblazer for progressive values. Now, this essay is not really the place for me to go into why this view was exaggerated2. Suffice to say, Gene Roddenberry never saw any reason to come clean about his real ambitions during the early days of Star Trek, ambitions that seem to have been humbler and more conventional than the legend he created suggests. No reason, either, to tell the truth about NBC, which was never as conservative as Roddenberry had fans believe3. Gene Roddenberry was such an inveterate self-mythologiser that I would not be surprised to find out that he came to believe his own tall tales.

In aesthetic terms, The Motion Picture is more explicitly utopian than The Original Series. The whites, light greys, tans and browns of the redesigned Starfleet uniforms for instance. And the civilians, with their skimpy, groovy outfits, certainly look dressed for the Age of Aquarius. The Motion Picture’s overtly utopian look dates it much more than any of the sequels or the later TV series. But it also makes it a fascinating document of its time.

Let’s return briefly to Tasha Yar’s Roddenberryesque funeral.

Now, as regards life after death, I don’t know what Roddenberry’s precise views were. Given that, as a teenager, he’d concluded that religion was “nonsense”, it seems likely his attitude was one of disbelief—at least for most of his 70 years.

In ‘vibe’ terms the Yar funeral scene blends humanism and New Age. The presence of the latter element is felt not only in the visuals but also in Ron Jones’s score. It’s a lush and dreamy piece of music, moving in places. The synthetic quality of parts of it chimes with the vaporwave unreality of that soundstage hill.

Jones’s most famous work was earlier released as a standalone album; only a snippet of it is included in The Ron Jones Project for copyright reasons. I refer to the score for the famous two-parter “The Best of Both Worlds”, with which TNG first experimented with a cliffhanger. Jones’s gloriously over the top climatic sting for the first part powerfully underscores Riker’s predicament, forced as he is into a course of action that might kill Captain Picard (who has been transformed into Locutus of Borg). Unfortunately though—considering the quality of “TBoBW” and other Jones scores—from the very first episode he worked on, “The Naked Now”, the composer encountered opposition to his musical vision from Berman and Lauritson, resistance that ultimately did not prove futile.

Jones has also released at least two New Age albums, proof of his strong affinity with that culture. Of course the composer hasn’t given himself over entire to the Age of Aquarius. His other credits include the music for Family Guy and American Dad!

IV

In part 1 I cited the season two episode “Where Silence Has Lease” as one that deals with the subject of death, even touching on the question of life after death. This is another episode that made a strong impression on the teenage Heg. It should be said that, like many episodes in seasons one and two, it’s rough around the edges. There is the occasional cringe moment. Yet it still warrants a close look because, thanks to one scene in particular, this episode is highly relevant to the subject matter of this essay. And even setting aside that scene, for me the episode as a whole is compelling for the level of imagination on display. Let’s examine it, then. It’ll be the last episode we look at in detail.

Memory Alpha reveals the title to have been taken from a line of the Robert Service poem The Spell of the Yukon. I know nothing about Service or that poem, so moving swiftly on…

The plot has the Enterprise exploring the “Morgana Quadrant”, an area of the galaxy not visited before by a manned vessel. The drama begins when Data detects a “hole” in space. Not a wormhole or anything similar—instead a void, a true void “without matter or energy of any kind”. Two probes sent into the hole disappear without trace. Wesley, who’s been promoted to helmsman, suggests they move closer. Picard concurs—unwisely as it turns out. The void suddenly expands and the Enterprise is enveloped. The crew are alarmed to now find themselves inside the cosmic aperture. “It’s like looking into infinity,” says Riker, gazing out at velveteen blue-blackness. There are no stars in sight.

The attempt to fly back out of the void proves unsuccessful. Wesley’s instruments show the Enterprise travelling at warp speed, yet there’s no visual indication the ship is moving—the view of “infinity” on the main viewer remains unchanged. At Data’s suggestion, a beacon is dropped to provide a fixed reference point. As the Enterprise moves away the pinging beacon recedes. But no sooner has the signal faded into nothingness than an identical signal is heard approaching from straight ahead. After a moment Data confirms the source to be the beacon, which is now in front of them. Though the Enterprise has been travelling in a straight line it has circled back on itself, like the player’s ship on the wraparound map of Atari’s Asteroids (1979).

What follows is a series of (initially) unexplained encounters and incidents. There’s an attack by a Romulan warbird, destroyed with suspicious ease by the Enterprise. The sister ship of the Enterprise-D, the Galaxy-class Yamato, approaches, but with no one on board (no life signs detected).

Riker and Worf beam over to find a dimly lit ghost ship constructed from unknown materials and with impossible, Escher-like topology. Communications with the Enterprise are cut off by apparent interference. On the eerily vacant bridge, Worf characteristically loses his cool when confronted with doors that lead off the bridge, back on to the bridge. Meanwhile a dilemma presents itself to Picard. A “star fix” appears on the Enterprise main viewer: a hole in the void, through which the stars are visible. The Captain would dearly love to take the proferred exit, but Chief o’Brien can’t get a transporter lock on Worf and Riker.

Of course Picard wouldn’t abandon his officers, so it’s not really a dilemma at all. The hole closes and the star fix disappears; immediately o’Brien gets a transporter fix on the away team and beams them back at the Captain’s command.

Doctor Pulaski, who has been watching events unfold on the bridge, is among the first to realise what’s going on: the hole in space the Enterprise is trapped in is in fact a laboratory. An entity of some kind is testing their responses to stimuli. Soon enough, this theory is proved correct, with the entity in question appearing on the main viewer. The bridge crew find themselves confronted by a strange, disembodied, vaguely anthropomorphic face. Yet, according to Data’s sensors, there’s nothing there. “Sure is a damned ugly nothing,” mutters Geordie from the back of the bridge.

The entity introduces itself as “Nagilum” (which is (almost) “Mulligan” backwards—actor Robert Mulligan was originally earmarked by producer Maurice Hurley to play the role, which instead went to Earl Boen). It soon becomes apparent that this entity is interested in many things, but what intrigues it most is human mortality. Seemingly out of pure curiosity, Nagilum kills the unfortunate “red shirt” who has replaced Wesley at the helm. “We cannot allow you to do that!” protests Picard, vehemently. “We will fight you.” But Nagilum is undeterred. It announces its intention to carry out a thorough investigation of death, “which should not require [the lives of] more than a third or a half of your crew.”

In the conference room, mulling over this dire prospect with the other officers, Picard proposes a radical course of action: destroy the Enterprise. With fighting such a powerful being as Nagilum apparently futile, the only possible response to the entity’s murderous plan is mass suicide. Naturally this idea raises a few eyebrows. “Why do I get the feeling this was the wrong time to join this ship?” Doctor Pulaski wonders aloud.

In engineering, Picard needs his First Officer’s consent to initiate the auto-destruct sequence. Riker gives it, persuaded of the rightness of the Captain’s desperate solution. The timer is set to twenty minutes.

The next scene opens with Picard in his quarters. The lights are dimmed, “Gymnopédie No. 1” by Eric Satie is playing quietly. Troi enters.

“Our destroying ourselves won’t change its mind, Captain. I would feel that.”

“You didn’t mention you were that certain.”

“I was wrong not to tell you. And your decision may also be wrong.”

The Counsellor sits down; Data enters.

“I have a question, sir.”

“Yes, Data, what is it?”

“What is death?”

“Oh, is that all?”

Patrick Stewart then goes on to deliver some of the most fascinating—and unexpected—lines in the whole of Star Trek: The Next Generation.

“Well, Data, you’re asking probably the most difficult of all questions.

Some see it as a changing into an indestructible form. Forever unchanging. They believe that the purpose of the entire universe is to then maintain that form in an Earth-like garden, which will give delight and pleasure through all eternity.

On the other hand, there are those who hold to the idea of our blinking into nothingness.

[Picard snaps his fingers]

With all of our experiences and hopes and dreams merely a delusion.”

Data: “Which do you believe, sir?”

[Picard smiles, not answering straight away, giving thought to his answer]

“Considering the marvellous complexity of the universe—its clockwork perfection, its balances of this against that, matter, energy, gravitation, time, dimension—I believe that our existence must be more than either of these philosophies. That what we are goes beyond Euclidean or other practical measuring systems and that our existence is part of a reality beyond what we understand now as reality.”

Whether intentionally or not, this extraordinary monologue builds satisfyingly on the ideas introduced in “Where No One Has Gone Before”: there is more to reality, to us, and to existence, than meets the Euclidean eye. The scene is thus another prime example of that New Age or mystical sensibility that enlivens, and deepens, Star Trek: TNG’s first two seasons.

The conclusion of that scene, and that of the episode, are worth mentioning. Troi has been oddly cold and stony-faced from the moment she stepped into Picard’s quarters. She doesn’t seem herself.

Once Picard has concluded his philosophical musings, she speaks up:

“We should not let ourselves die, Jean-Luc.”

“I agree with her… Jean-Luc.”

Data’s use of Picard’s given name is especially jarring. But then so was his initial question about death: a naïve and childlike thing to ask, even for him. Picard realises there’s something up:

“Neither of you should be reacting in this way.”

The Captain asks the Enterprise’s computer to locate Commander Data—he turns out to be on the bridge. Picard gives a slight shake of his head.

“It’s not going to work, Nagilum.”

Realising the game is up, Nagilum dispenses with the bogus Data and Troi. They vanish. A moment later the real Data pipes up to deliver some very good news:

“Captain, we are clear. We are out of the void.”

Sure enough, when Picard looks out of the nearest window, he sees stars. Yet he doesn’t cancel the auto-destruct sequence immediately, as Riker urges.

On the bridge, Picard orders the Enterprise to go to warp 6, any heading. Then he waits. The bridge crew become increasingly alarmed as 30 seconds becomes 20 seconds becomes 10 seconds. Finally he relents. When the computer invites Riker to provide consent for the cancellation of auto-destruct, he concurs “wholeheartedly”.

Picard has one last encounter with Nagilum. The entity appears on the Captain’s personal terminal in his ready room. After some less than warm words the two agree their species have at least one thing in common: curiosity.

“Where Silence Has Lease” isn’t considered one of the greatest TNG episodes, but remains a favourite of mine. I hold a minority view of TNG generally, preferring the less well-regarded seasons one and two to later seasons, when these fascinating spiritual and mystical themes we’ve been exploring disappeared from the series, dematerialising as surely as an unfortunate red shirt hit by a phaser beam set to kill. Precisely why that happened is a question I attempt to answer in the third and final part of this essay.

Those unfamiliar with Rick Berman may appreciate a little background information on the man, especially given his absolutely key role in the TNG story. Here’s Larry Nemecek in The Star Trek: The Next Generation Companion (Pocket Books, 1991, 1995, 2003):

Having begun in the fall of 1986 as the studio’s TNG liaison, Berman came aboard early in 1987 to take over for [first TNG producer Eddie] Milkis, who had decided to check out early on his one-year contract.

..

Berman had come to Paramount from Warner Brothers in 1984 and performed a succession of studio roles: director of current programming, executive director of dramatic development, and finally vice president of “longform and special projects”—miniseries, TV movies, and then “the new Star Trek.” He shared the title of supervising producer with [TOS veteran producer Bob] Justman as “Encounter at Farpoint” prepared to shoot.

“I had been Paramount’s ‘studio guy’ for the series for about two weeks when Gene Roddenberry asked me to lunch, and it was love at first sight,” Berman recalled. “He went to the studio and said, ‘Can I have him?’ and they said yeah.” And that, he added warmly, was the beginning of a relationship with GR that was “very special,” although at the time Berman had no idea he’d end up as the “new” Great Bird in a few years.

Lance Parkin’s The Impossible Has Happened (Aurum Press, 2016), an unofficial Gene Roddenberry biography, offers a decent account of the early days of Trek fandom. The book recounts how a rather fanciful mythology developed around Star Trek and its creator, one in which Roddenberry had had to battle the network, NBC, at every turn. For instance, Roddenberry began claiming that the network had not been keen on having what we would now call a diverse cast. In fact the opposite was the case—NBC, like most major television networks at that time, was keen to show how progressive it was, and was all in favour of diverse casting.

In the first volume of Edward Gross and Mark A. Altman’s The Fifty-Year Mission, subtitled The Complete, Uncensored, Unauthorized Oral History of Star Trek: The First 25 Years (St. Martin’s Press, 2016), the much-maligned producer for the third season of TOS, Fred Freiberger, claims that season’s celebrated interracial kiss between William Shatner and Nichelle Nichols actually had nothing to do with Roddenberry:

I read an article, which I think was in the L.A. Times, praising the episode “Plato’s Stepchildren” as the first television show to allow an interracial kiss. A breakthrough. Roddenberry was lauded for this, when in fact Roddenberry wasn’t within a hundred miles of that episode.

The reason the Trek creator wasn’t within a hundred miles was that he’d stepped back from the show for season three, refusing to produce it, ostensibly in protest at NBC having moved it to the “graveyard slot” of 10PM on Fridays. He wasn’t totally uninvolved—he still watched footage, issued memos and so on—but there do seem to have been some episodes made without Roddenberry’s input.

Really enjoying this soon-to-be trilogy of pieces on ‘Star Trek TNG’. It’s always a pleasure to read a thought-provoking and indeed invigorating reading of a television series I’ve loved since childhood more or less. Perhaps for some aesthetic reason or other I was always drawn slightly more to TOS as a youngster, but I’ve always felt that TNG drew even deeper from the popular intellectual tendencies of the ‘60s than even TOS, albeit refracted through a ‘80s lens, something which always struck me as quite daring for a mainstream show in an era one (perhaps lazily) associates with a general recession from the idealism of the 1960s. Perhaps the association with the original helped incubate its ‘60s-ish/New Age tone…

Anyway, I’ll spare any further banal thoughts on my part, but I just wanted to ask on the subject of television whether you had ever given much thought to my favourite 1960s programme, Patrick McGoohan’s ‘The Prisoner’? I feel that it vibrates to many of the same rhythms to the things you write about here…