#30 From the Twitter archives, part 12D: Daily Modernist series, thinkers

Three 20th-century innovators.

Max Weber

1864—1920. Sociologist, philosopher. Alongside Karl Marx and Émile Durkheim, Weber is considered one of the three founders of sociology. In contrast to Durkheim, Max Weber was an antipostivist, and sought to understand social action through interpretative means, not purely empirical ones—he asked what purpose and meaning individuals attached to their actions.

One of his most famous ideas is that modern societies possess a “stahlhartes Gehäuse” (steel-hard casing)—also translated as ‘iron cage’—of rationalism and bureaucracy, which the individual experiences as profoundly oppressive. Kafka explored a similar idea in his fiction.

For Weber, the iron cage was part and parcel of the “disenchantment of the world”. While Weber’s view of modernity is thus a melancholy one, he analysed his era in a resolutely modern way.

Another well-known idea of Weber’s is that capitalism is Protestant in spirit, a theory he laid out in his most famous work The Protestant Ethic and the “Spirit” of Capitalism1. The Protestants had sought to turn the world into wealth for the glory of God. Accumulated riches as evidence of being among God’s elect. An idea that helps us understand America’s individualist and workaholic tendencies.

The Reformation, for Weber, brought a revolution in the view of work,with even the most mundane professions now seen as contributing to the common good; primarily Catholic societies held on to older attitudes. An extract from Weber’s Wikipedia page:

Weber put forward the thesis that Calvinist ethic and ideas influenced the development of capitalism. He noted the post-Reformation shift of Europe's economic centre away from Catholic countries such as France, Spain and Italy, and towards Protestant countries such as the Netherlands, England, Scotland, and Germany. Weber also noted that societies having more Protestants were those with a more highly developed capitalist economy. Similarly, in societies with different religions, most successful business leaders were Protestant. Weber thus argued that Roman Catholicism impeded the development of the capitalist economy in the West, as did other religions such as Confucianism and Buddhism elsewhere in the world.

Weber made studies of various religions, including ancient Judaism (in a book of that title), and it’s interesting to take Weber further and speculate (as the early Marx did) on how Jewish attitudes may interact with Protestant ones in capitalist societies: something to be explored in another post.

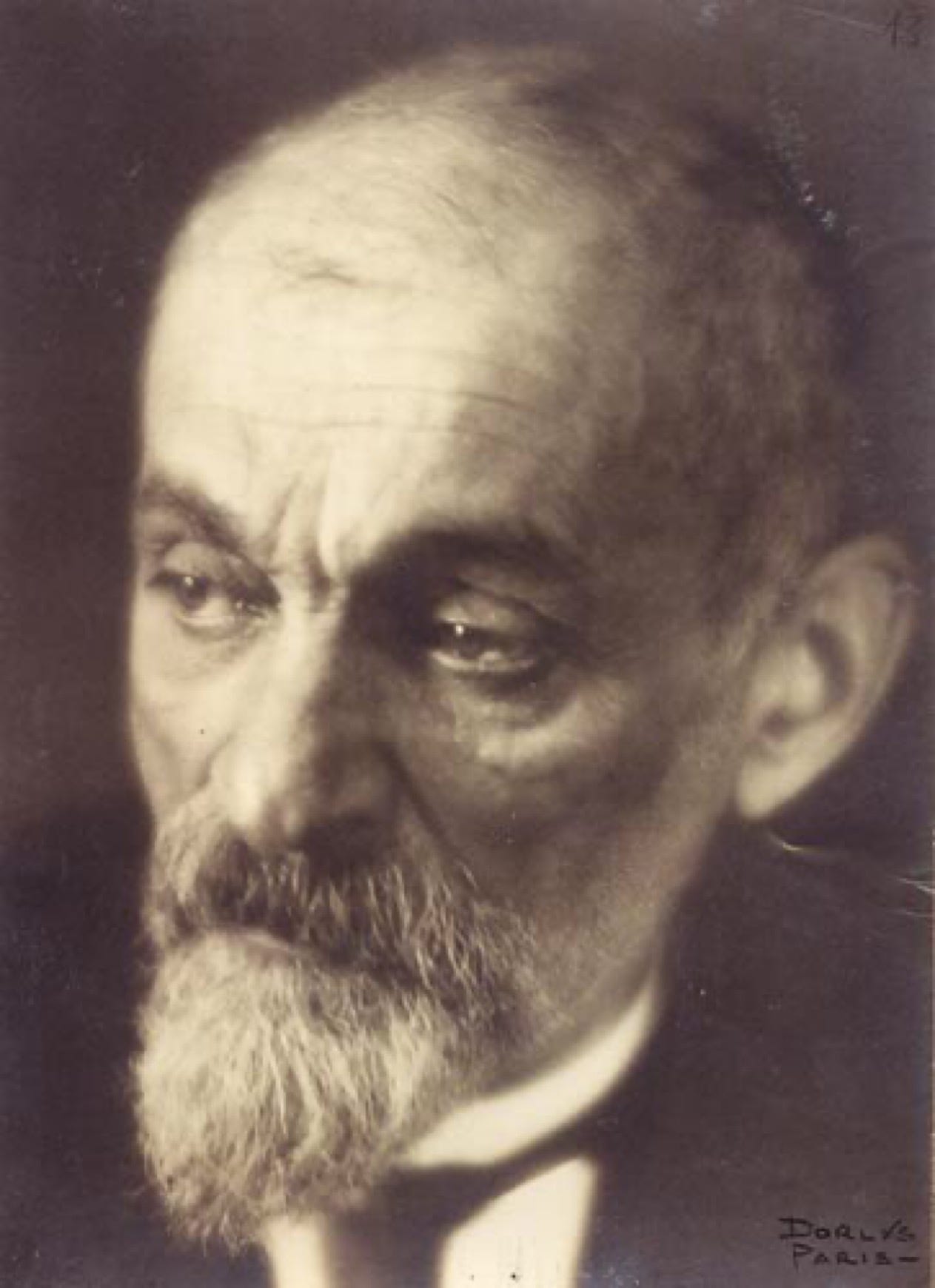

Lev Shestov

1866—1938. Philosopher. A Russian Jew who accepted the resurrection of Christ, Shestov was a radical thinker who believed philosophy should dispense with reason. For Shestov rationality was misleading and, in the age of science, increasingly tyrannical.

“Everything is possible.” This wasn’t a utopian claim but rather an affirmation of life’s arbitrariness and strangeness. Shestov believed that the cosmos only appears to be coherent: reason conceals its inexplicability. This belief connects him unexpectedly with Jarry and pataphysics.

Here’s the opening of Shestov’s opus, Athens and Jerusalem (I consider it worth quoting at some length)2:

We live surrounded by an endless multitude of mysteries. But no matter how enigmatic may be the mysteries which surround being, what is most enigmatic and disturbing is that mystery in general exists and that we are somehow definitely and forever cut off from the sources and beginnings of life. Of all the things that we here on earth are the witnesses, this is obviously the most absurd and meaningless, the most terrible, almost unnatural, thing—which forces us irresistibly to conclude either that there is something that is not right in the universe, or that the way in which we seek the truth and the demands that we place upon it are vitiated in their very roots.

Whatever our definition of truth may be, we can never renounce Descartes’ clare et distincte (clarity and distinctness). Now, reality here shows us only an eternal, impenetrable mystery—as if, even before the creation of the world, someone had once and for all forbidden man to attain that which is most necessary and most important to him. What we call the truth, what we obtain through thought, is found to be, in a certain sense, incommensurable not only with the external world into which we have been plunged since our birth but also with our own inner experience. We have sciences and even, if you please, Science, which grows and develops before our very eyes. We know many things and our knowledge is a “clear and distinct” knowledge. Science contemplates with legitimate pride its immense victories and has every right to expect that nothing will be able to stop its triumphant march. No one doubts, and no one can doubt, the enormous importance of the sciences. If Aristotle and his pupil Alexander the Great were brought back to life today, they would believe themselves in the country of the gods and not of men. Ten lives would not suffice Aristotle to assimilate all the knowledge that has been accumulated on earth since his death, and Alexander would perhaps be able to realize his dream and conquer the world. The clare et distincte has justified all the hopes which were founded upon it.

But the haze of the primordial mystery has not been dissipated. It has rather grown denser. Plato would hardly need to change a single word of his myth of the cave. Our knowledge would not be able to furnish an answer to his anxiety, his disquietude, his “premonitions.” The world would remain for him, “in the light” of our “positive” sciences, what it was—a dark and sorrowful subterranean region—and we would seem to him like chained prisoners. Life would again have to make superhuman efforts, “as in a battle,” to break open for himself a path through the truths created by the sciences which “dream of being but cannot see it in waking reality.” In brief, Aristotle would bless our knowledge while Plato would curse it. And, conversely, our era would receive Aristotle with open arms but resolutely turn away from Plato.

Guy Debord

1931—94. Theorist, filmmaker, board game designer. One of the most brilliant thinkers of his generation, Debord first became politically and theoretically active with the Letterist International. A Parisian avant-garde movement of the 40s and 50s, the L.I. took inspiration from Dada and Surrealism.

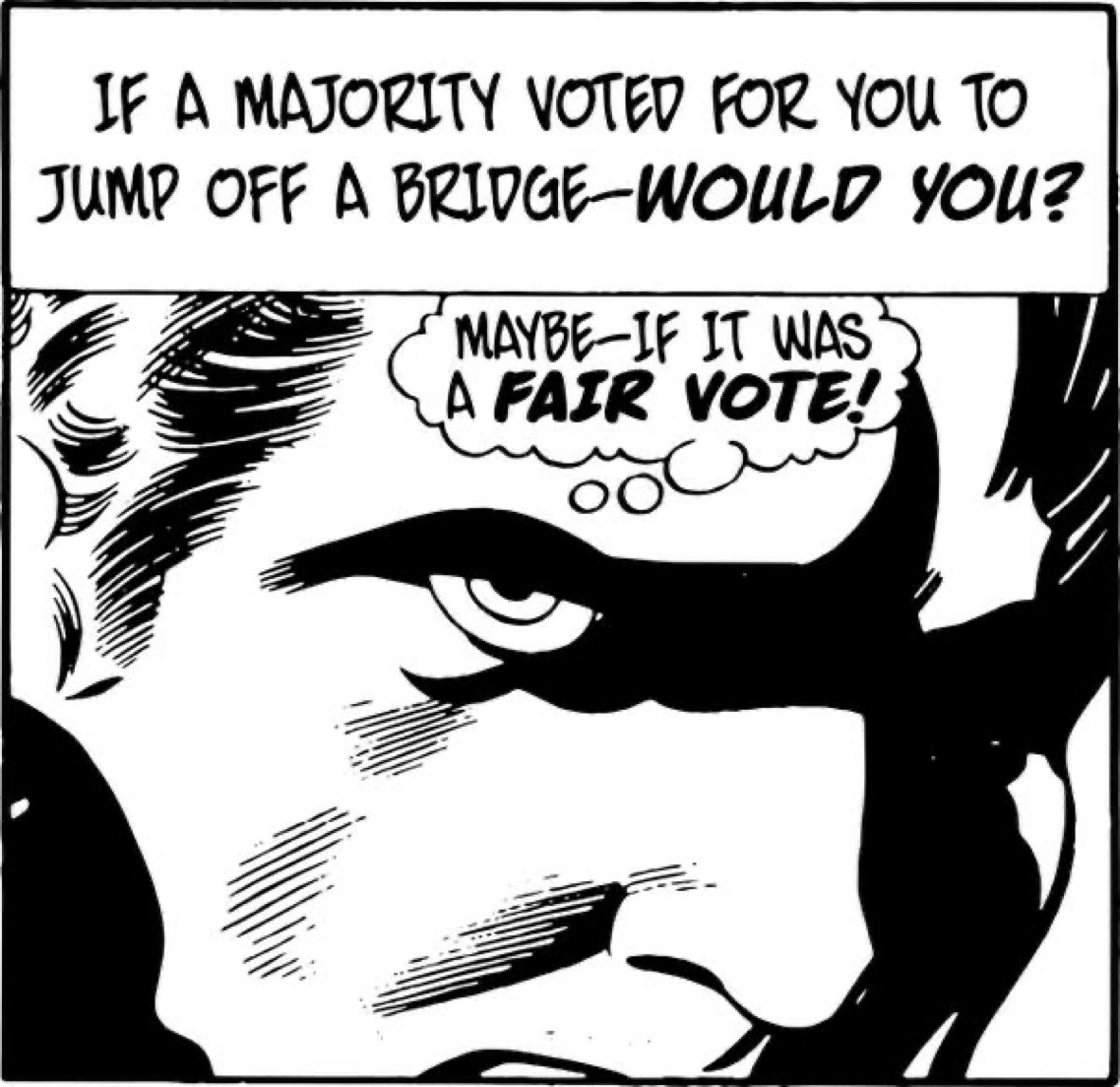

These influences would be key to the group Debord went on to found and lead in the 60s, the Situationists, who combined Marxism with anarchism. Their name came from their practice of creating ‘situations’—poetic disruptions of everyday banality intended to awaken and liberate.

Debord’s main theoretical contribution was The Society of the Spectacle3, in which he defined a kind of unreality, engendered by capital, that had taken over the modern societies of both East and West (the Soviet system he considered ‘bureaucratic capitalism’). The familiar opening few theses (the reader will note the obvious influence of Marx, but the idealist strain in Debord’s thought is more Hegelian):

1. In societies where modern conditions of production prevail, all of life presents itself as an immense accumulation of spectacles. Everything that was directly lived has moved away into a representation.

2. The images detached from every aspect of life fuse in a common stream in which the unity of this life can no longer be reestablished. Reality considered partially unfolds, in its own general unity, as a pseudo-world apart, an object of mere contemplation. The specialization of images of the world is completed in the world of the autonomous image, where the liar has lied to himself. The spectacle in general, as the concrete inversion of life, is the autonomous movement of the non-living.

3. The spectacle presents itself simultaneously as all of society, as part of society, and as instrument of unification. As a part of society it is specifically the sector which concentrates all gazing and all consciousness. Due to the very fact that this sector is separate, it is the common ground of the deceived gaze and of false consciousness, and the unification it achieves is nothing but an official language of generalized separation.

4. The spectacle is not a collection of images, but a social relation among people, mediated by images.

5. The spectacle cannot be understood as an abuse of the world of vision, as a product of the techniques of mass dissemination of images. It is, rather, a Weltanschauung which has become actual, materially translated. It is a world vision which has become objectified.

6. The spectacle grasped in its totality is both the result and the project of the existing mode of production. It is not a supplement to the real world, an additional decoration. It is the heart of the unrealism of the real society. In all its specific forms, as information or propaganda, as advertisement or direct entertainment consumption, the spectacle is the present model of socially dominant life. It is the omnipresent affirmation of the choice already made in production and its corollary consumption. The spectacle’s form and content are identically the total justification of the existing system’s conditions and goals. The spectacle is also the permanent presence of this justification, since it occupies the main part of the time lived outside of modern production.

Debord’s career petered out after the 60s. He made a curiously hypnotic film to accompany tSotS (viewable on YouTube), and even designed a board game simply titled War, but didn’t produce anything else of note. The Situationist International disbanded in 1972. In ‘94 Guy Debord committed suicide.

Weber, Max, The Protestant Ethic and the “Spirit” of Capitalism, translated by Baehr, Peter and Wells, Gordon C. Originally published in German in 1905. This translation: Penguin Books 2002.

Shestov, Lev, Athens and Jersualem, translated by Martin, Bernard. Originally published in Russian 1930-37. This translation: Ohio University Press 1966, 2016.

Debord, Guy, The Society of the Spectacle, translated by ‘Black & Red’. Originally published in French in 1967. This translation is copyright free.

Interesting

I never knew about the Debord Board Game, although someone is currently organising a game of Asger Jorn's Three-Sided football in Glasgow.