#27 From the Twitter archives, part 12A: Daily Modernist series, musicians

Revisiting a series of threads on prominent modernist figures.

Introduction

For a few weeks in 2020 I ran a series called Daily Modernist. My first choice was Bela Bartók; the thread for him was very short, only two posts. As the series progressed the threads quickly grew longer. I wanted to do justice to the figures I picked, while at the same time remaining concise. However, after the first few my Daily Modernists weren’t as daily as I’d have liked, and after fifteen entries I concluded the series was too ambitious and suspended it. I still like the threads I produced, though, so here they are in Some Private Diagonal form.

By no means all the figures I’ll present will be canonical modernists, that is, individuals recognised as modernists by academia. However, they’ll all be bold innovators who displayed a fascination with one or more aspects of the modern world (without necessarily being all that fond of modernity as a whole—there was in fact a very important strain of modernism that was antimodern).

The modernists will be grouped by specialisation. We begin here with two musicians.

..

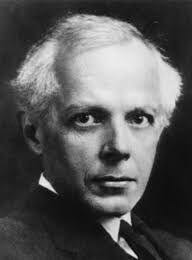

Béla Bartók

1881-1945. Composer, pianist. Bartók incorporated folk melodies from his beloved Hungary into his music. As with other 20th-century composers with nationalist leanings, this mining of a folk tradition was a response to the breakdown of the diatonic system of harmony that had served Mozart, Beethoven et al. Bartók also embraced avant-garde dissonance, though more subtly than did radical contemporaries like Schoenberg. Raised a Catholic, Bartók became first an atheist and later a Unitarian. He was said to be a great lover of nature.

Daphne Oram

1925-2003. Musician, composer. What does a circle sound like? Or a square, a triangle? This is what Daphne Oram wondered as a schoolgirl in the 30s, as she dreamt of a device that’d allow her to draw sound, draw music.

Her journey towards realising this vision began at the BBC during the war, where she was tasked with producing sound effects. After hours she’d experiment with tape recorders long into the night.

In France at the same time two Pierres, Henry and Schaeffer, were conducting similar experiments, producing what they called musique concrète. In 1958 Oram cofounded the BBC Radiophonic Workshop with Desmond Briscoe. The Beeb was producing avant-garde radio plays by the likes of Samuel Beckett and needed unusual music and sound effects. Electronic instruments barely existed then, so the Workshop had to experiment every which way to come up with the goods.

Oram believed electronic music should become the BBC music department’s main focus but the department refused, so she left the Radiophonic Workshop after less than a year. She set up her Oramics Studio in a converted Oast House in Kent and, with the help of her brother John Oram and an engineer, Fred Wood, set about building her Oramics Machine, the device that would allow her to draw sound as she’d envisaged decades before.

The finished machine took lines and shapes drawn onto 35mm film stock and turned them into sound.

Oram’s music is by turns playful and unsettling, even disturbing.

Her work can be heard in the 1961 film The Innocents, an adaptation of Henry James’s ghost story novella The Turn of the Screw. The eerie otherworldliness of Oram’s sounds is remarkable, and at the time cinema-goers had never heard anything like it.1

I heartily recommend Wee Have Also Sound-Houses, a BBC Radio 3 documentary on Daphne Oram originally broadcast in 2008.