#26 From the Twitter archives, part 11: Concrete and Glass

J.G. Ballard’s most visionary and provocative era.

Towards a benevolent psychopathology

Do you want to know why Ballard’s late 1960s and 1970s output is based? Because it’s all about unstoppable civilisational decline, and the chances of thriving, despite everything, in the midst of it. Ballard’s radical proposition is that decline and dissolution even open up new, undreamt-of possibilities.

Logic of the landscape

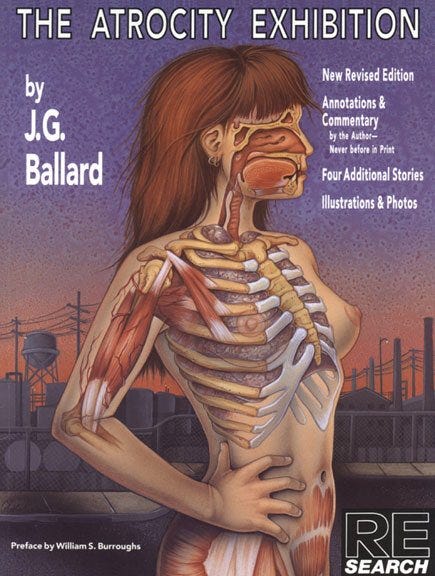

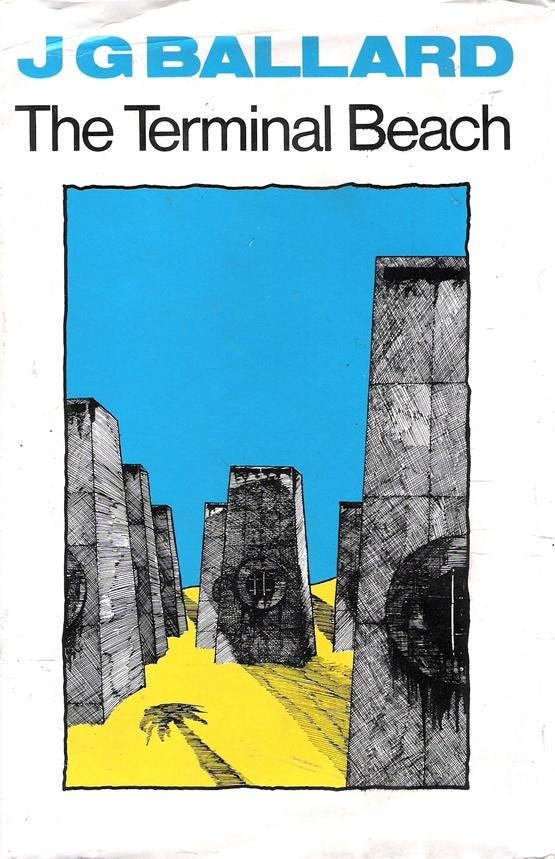

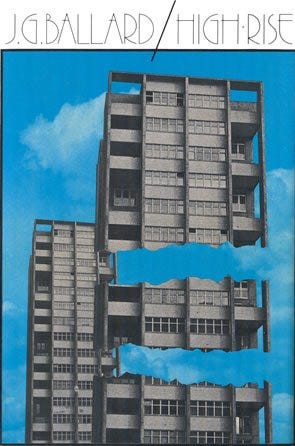

Getting off to a tentative start with 1964’s short The Terminal Beach and ending with the 1975 novel High Rise, this is what’s generally regarded as Ballard’s most radical era. Although there’s a case to be made that The Atrocity Exhibition and Crash are sui generis, the “concrete and glass” period as a whole bears comparison with the work of the Futurists and that of Wyndham Lewis. Parallels can also be drawn with the Oswald Spengler of Man and Technics.

Lunar and abstract

Decades later, in a departure from this broadly (though certainly not trad) Right-wing position of the 60s and 70s, Ballard became moderately Left-wing—as he himself confirmed in interviews. But it’s the concrete and glass era that is, for me, the most compelling. It’s the strange combination of optimism (at the individual level) and pessimism (at the social level) that makes this work fascinating.

Tolerances of the human face

Ballard’s motives for writing these works seem ambiguous. Is this the author as moralist, as responsible social critic—or something darker? The answer of course is that it’s both. The self is a spectrum of spiritual possibilities, and the writing of a work will involve many of these.

Operating formula

An interesting question is Ballard’s position vis-à-vis modernism and postmodernism. The heavy use of scientific terms and the clinical prose style would seem to mark him as a modernist. Yet Ballard said he used these terms to achieve a certain effect, and spoke of “so-called” reality.

Ballard certainly doesn’t ignore or dismiss science as postmodern theorists are wont to do. He seems to think science (which one character calls “the ultimate pornography”) is broadly true, but missing something: it contains no account of “the unseen powers of the cosmos”.

Casting the runes

Ballard admirer Iain Sinclair speaks of the author and his work in terms the man himself never did. He calls JGB ”a magus” and writes of the texts collected in The Atrocity Exhibition: “No one could be expected to act on these instructions; they were magical and threatening to the fabric of the received world.”1

There is, perhaps, an element of hostile intent in Sinclair’s commentary: this is an attempt to remythologise Ballard, to remove him from the modernist / science-fiction frame in which he presented himself, in order to place him definitively within Sinclair’s preferred frame of occultism. To some extent this has succeeded.

Addendum

The following text is taken, slightly altered, from a later thread.

Modulus of pain and desire

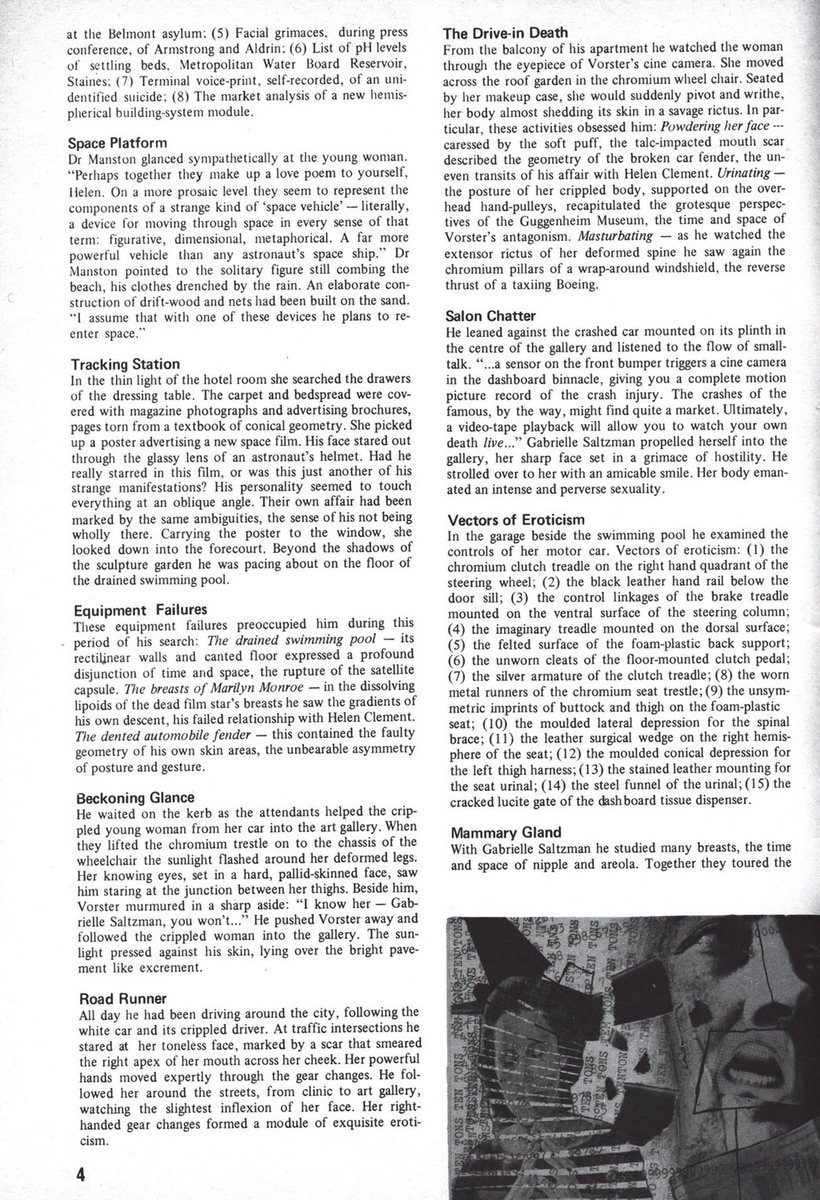

This section will look at a lesser-known story from Ballard’s concrete and glass period. This piece, “Journey Across A Crater”, dating from 1970, is for some reason not included in the second volume of the so-called Complete Short Stories, which covers this period of Ballard’s work.

Exit wound

As is typical with the ”condensed novels” of this period (the others are collected in The Atrocity Exhibition), it’s not immediately clear what’s going on. We have a protagonist, here unnamed, whom a young woman, Helen Clement, sees “appear [in the urban landscape]..like a drowned archangel.”

Ballard’s stories of the period 1964 to 70 stand out in his work in that they quite often present explicitly religious, Christian images. Archangels also appear in TAE, alongside images of the Virgin, and even a Christlike figure (whose Second Coming is, however, botched).

Alien obsessions

The sentences are compressed, hard, angular. Ballard observed in an interview that his prose tended to take on the qualities of the landscapes it was describing. His prose in his earlier novel of catastrophe, The Drought, thus has a certain arid quality Ballard didn’t care for.

The aggressively active cripple, Gabrielle Saltzman, is clearly a focus of erotic fascination. During this period Ballard was obsessed with life’s victims—and how they sometimes, in a perversely original move, embrace their irreversible misfortune, and in so doing transcend their victimhood.

Music of the quasars

But what is the lead character trying to do? Seems that, like the T character in TAE, he’s having a breakdown (which may be a liberation). He moves through the external world but also through his own consciousness. Like the author, he follows his obsessions—he senses that these hold the key.

Perhaps what all Ballard’s protagonists are searching for is simply transcendence, ie God (in our Western understanding). And sometimes they find it, though in these concrete and glass stories it’s more often a negative transcendence that they attain—the transcendence of Evil?

Sinclair, Iain, Crash, BFI Modern Classics, 1999.