#41 Gradually Learning

An interview with The Rockingbirds' Alan Tyler

“Life may be sad, but it’s always beautiful.” So observes Jean-Paul Belmondo to Anna Karina in Godard’s Pierrot le fou (1965). After I’d finished it, English country musician Alan Tyler’s memoir How To Never Have A Hit got me thinking about that film and that line. For Tyler’s book is not only, as its title suggests, melancholic. It’s also beautifully written, in a low-key, understated way. At a time when traditional publishing has arguably reached its nadir, this memoir is a welcome demonstration that something truly worthwhile can appear from an unexpected quarter.

The author is modest about his self-published work, describing it as “an entertainment, a comedy about a fairly inconsequential person, fumbling through life, full of illusions, making mistakes, but also making discoveries and connections and achieving a few things.”

However, as Tyler freely acknowledges, readers of this memoir may well take its author for un fou, a madman. At the time, many associates questioned the sanity of a man resolved to try and forge a country music career in Britain. Furthermore, by the author’s own admission, his is a story in which self-sabotage appears to play a not-insignificant role.

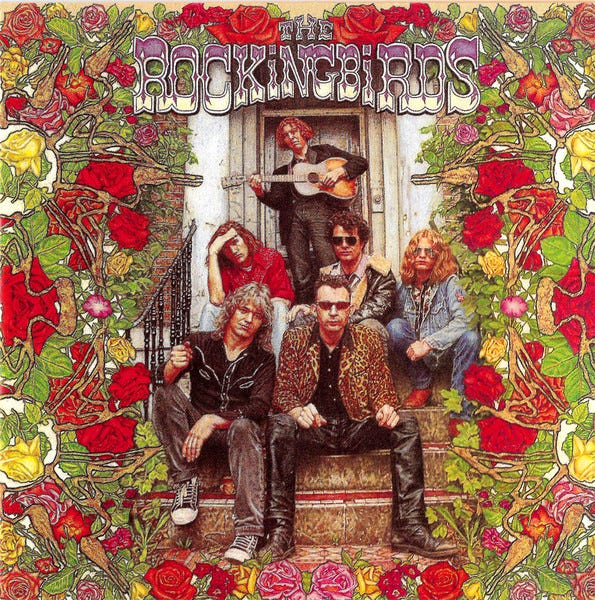

Hailing from Kenton in northwest London, Alan Tyler went from punk experiments and fanzine production in his teens in the late 70s to founding country band The Rockingbirds a little over a decade later. The group was six-strong, with Tyler as the outfit’s singer-songwriter, acoustic guitarist and leader. Hip label Heavenly put out The Rockingbirds’ eponymous debut LP in ‘92; though well reviewed, it didn’t trouble the album charts. Their only semi-hit single was not even their own, being a cover of Right Said Fred’s “Deeply Dippy” recorded for a charity record.

Follow-up LP Whatever Happened to the Rockingbirds emerged in ‘95, with sales still more underwhelming than those of their debut. This lack of commercial success (which to some extent the group’s leader blames himself for), and the band’s split that year, compelled Tyler to take a different course in life. In an echo of John Hartford’s song In Tall Buildings, covered on The Rockingbirds, the singer-songwriter took up office work, continuing his music career as a modest side hustle.

How To Never Have A Hit relates this whole story: not only the compelling, funny, sometimes moving details of The Rockingbirds’ (mis)adventures but also Tyler’s experiences as just another normie on the PAYEroll, first for a small London “media” business staffed by oddballs, later for the civil service under both Labour and the Conservatives. We also learn some melancholy details about Tyler’s personal life, plus a few bright ones.

Despite having been a full-time employee of HM Government, Tyler has had quite an eventful 21st century on the music front: he’s pursued a solo career and managed a popular, London pub-based weekly folk and country event. He’s also reformed The Rockingbirds—this he did in the early 2010s. Of especial interest toward the end of the book is Tyler’s account of how, by closing down his social media accounts, he “cancelled” some of his more tiresome left-wing associates before they cancelled him.

Alan Tyler generously allowed me to interview him about his life and career, and his experience of writing How To Never Have A Hit.

PH: Why country music, an American genre? Does it have another meaning for you, evoking England, the English countryside?

AT: I very much took the punk rock “destroy all rock-n-roll” rhetoric at its word, so after a few years of being into “new wave” that scene quickly exhausted itself for me and in the mid 80s I cast about for other things, something different, ending up in a swingy pop group called Take It. Country proved my next rich “unmined resource” It hadn't really been done before at all by a British group, with fairly obscure exceptions: Brinsley Schwartz, the Downliners Sect.

It could’ve been something huge, like the Beatles and the Stones selling r’n’b back to the Americans. That was the idea, but of course it didn’t happen. More recently, yes, I came to investigate the "English country garden”, as it were. The rural history that haunts the urban present. My song "Somewhere Better” is literally a country song in that it is a song about a country, or more accurately, a kingdom, a nation state, and the lives and aspirations of the people in it.

Which songs are you proudest of?

“The Blue Man” [a late 90s song, which Alan recorded as part of a short-lived duo called Famous Times] is a one that stands out, and so is the Rockingbirds’ Gradually Learning. But both are long and slow to get going, which counted against them commercially. When Sony wanted a shorter version of Gradually Learning for the single and video, I went to the mastering and edited out the middle eight, because I was too fond of the instrumental ending. Producer Clive Langer was aghast!

“Down On Deptford Creek” I am proud of. Descriptive lyrics - a river poem. “Jonathan Jonathan” [a tribute to the Modern Lovers’ Jonathan Richman, which Alan got to play in person to his hero] is probably rightly my best known song. Pointless presenter and million selling author Richard Osman knows all the lyrics, someone told me. Maybe they were twitting me. A Rockingbirds urban myth.

I like my El Tapado electronic album a lot.

Like many musicians I am fonder of my later efforts, while others prefer the old stuff!

I think I’ve a "realistic" take on my strengths and weaknesses. My stuff has merit, but I am not saying it deserved to do better than it did. I can turn my hand to lyrics when I get a strong idea, but my talent as an instrumentalist and composer is technically limited; this I overcome by conning good musicians to work with me. Ha ha.

The title of the book suggests it lays out a recipe for not being a commercial success. You do express some regrets in there and mention a “self-destructive impulse” at work. Is that how you see it?

Yes. With The Rockingbirds we were chasing success, but I was running away from it at the same time, which is what my Agoristo chapter is about [the chapter describes how a mysterious dream Tyler had turned into an obsession]. Even my book title is deliberately “wrong”, it’s a bit of a no-no to express a negative if you are trying to sell something. I’m still self-sabotaging! I did offer "Gradually Learning” as a more positive alternative, but publishers remained uninterested. Gradually Learning can be the film title. Ha ha.

The bits about your “normie” work in the book are no less interesting than the rest. The part about Speedex I found fascinating: one of those small, strange, vaguely seedy enterprises that generally go unnoticed. I didn’t even know that kind of work [recording TV mentions of firms onto VHS and sending the tapes to those firms to get paid] existed.

That's good. Thanks. The Speedex section is one which I am particularly pleased with. I deal with civil service/corporate culture in another chapter.

“It was always Year Zero in the civil service” is a horrifying sentence, though perhaps not surprising. It casts an ironic light on Yes Minister, where Sir Humphrey and pals always wanted to maintain the dysfunctional status quo.

I was too low down to see much of Sir Humphrey’s Machiavellian chicanery, but saw lots of sclerotic corporate audit culture.

Could you say something about W G Sebald and Mark Fisher, who you’ve mentioned to me as influences?

I wrote a diary of a walk I did of the North Norfolk coast, which got featured on the Caught By The River website. Afterwards somebody told me it was reminiscent of Sebald’s Rings Of Saturn, so I read it with great interest along with Austerlitz - now favourite books of mine. My use of photos without captions is straight out of Sebald. In a few places, I have tried to make amusing or strange connections between obscure individuals and places and greater things, historic events, which is a Sebaldian thing, maybe.

Regarding Mark Fisher, I didn’t know anything about him until after he died. I make use of his “Slow Cancellation of the Future” talk in the last “Yesterday’s Chips” chapter to explain how music has lost its history-making, genre generating power, leaving us with endless reiterations of similar things. There is still good new music but not the great movements of the past. The book touches on cancel culture, a subject on which Fisher blazed a trail with his [Exiting the] Vampire Castle essay. Fisher also wrote about the Kafkaesque hell of managerialism and HR in Capitalist Realism, drawing from his own experience in teaching. In my experience the civil service put huge energies into creating the appearance of improvement and value, often with negative impacts on reality. I write about empire building managers in their remote realms of trusted data and expert advice always wanting “more resources”. Paula Vennells at the Post Office was typical of all that, not an aberration, as people want to think.

To be fair, Fisher had no solutions, and now we have a Republican US president and his side-kicks taking over, who are committed to tearing down the bureaucratic anti-production that Fisher criticised!

In the book, though, you relate how appalled you and your friends were by Trump’s shock win in 2016. Would you say your view of him, and your politics generally, have shifted over the past 8 years?

I still think Trump is narcissistic and very post-truth; what changed is I no longer think the opposition is better. Trump’s lies have tended to be capricious and self-serving, but the Democrats and their supporters everywhere are committed to stupid stuff that is institutionalised and culturally dominant, and as CS Lewis observed, it may be better to be ruled by a selfish tin-pot dictator than by legions of politicised people who will never give you a moment’s peace because they are doing it for your own good.

What next for Alan Tyler?

A few Rockingbirds gigs in 2025 are planned. I am also working on a show which will intersperse readings from the book with songs from my career, almost like a little musical.

I must admit, I have no present ambition to make more albums. I am feeling, once again, that my work is almost done, as I did in 1992 after our first album was recorded. I'm feeling a bit Agoristo.. wanting to have my day and disappear.

Leave new music to the youngsters. Good luck to them, they need it. As I say in the book, the up-escalator for bands has broken down. A large part of the eco-system in which bands thrived has gone.

Come to think of it, even the prospect of “having a hit”, a popular song that most people can hum or whistle, is outmoded, something that belongs to 20th century mass culture – the whole family sitting round the telly, watching Top Of The Pops. It’s over. Hits are things that haunt us from the past. Every Christmas, the same ones! Could AI write a huge hit? Perhaps we will never know. I don’t think so. More likely it will churn out Huxleyan aural wellness balm, on tap as it were, on subscription, or on prescription.

What does he mean by Agoristo?