#31 From the Twitter archives, part 12E: Daily Modernist series, writers

A trio of stunningly imaginative talents.

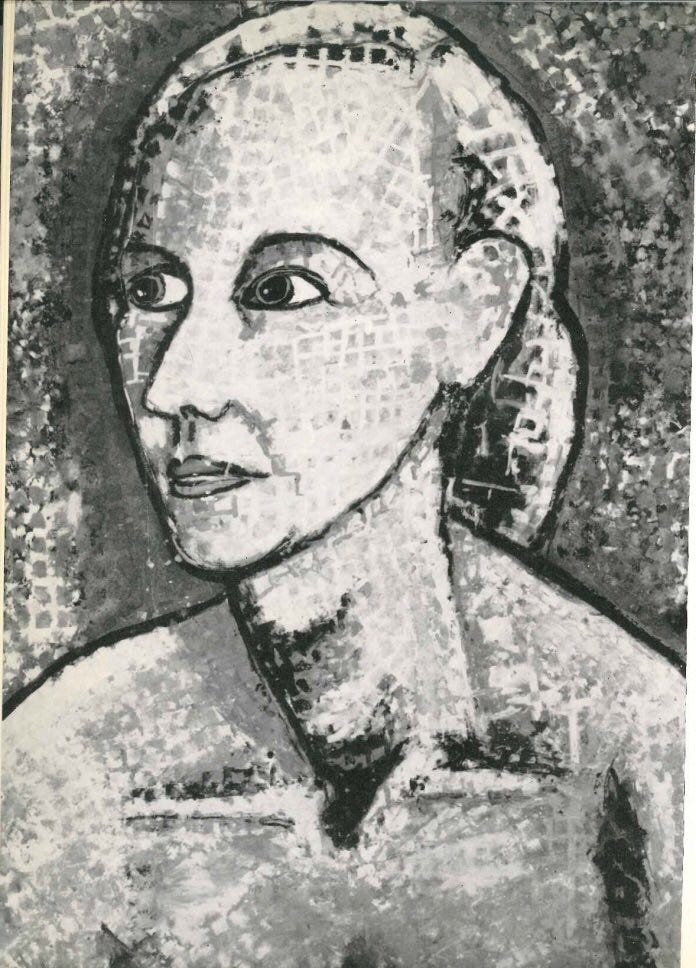

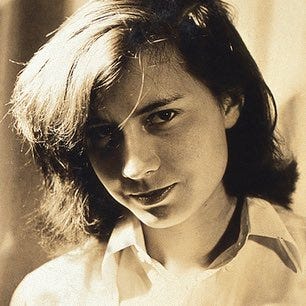

Anna Kavan

1901—68. Novelist, painter. Helen Emily Woods published six novels under the name she acquired by her first marriage, Helen Ferguson. Her second marriage, like her first, failed, and she emerged from a spell in an asylum as Anna Kavan, the platinum blonde heroine of two of her novels.

As Kavan she became an avant-garde writer and painter, publishing novels and short stories possessed of a unique, intense, disturbing poetic vision. She was a long-term heroin addict, but her prose always remained sharp, classically weighted, icily precise.

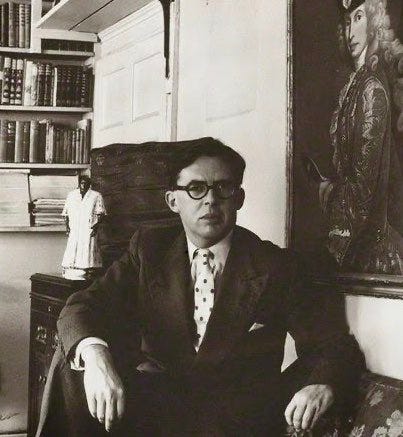

Robert Aickman

1914—81. Short story writer, novelist, conservationist. Another controversial choice: Aickman was often scathing about modernity in his writings, but he’d probably agree there was little that was traditional about his approach to supernatural fiction.

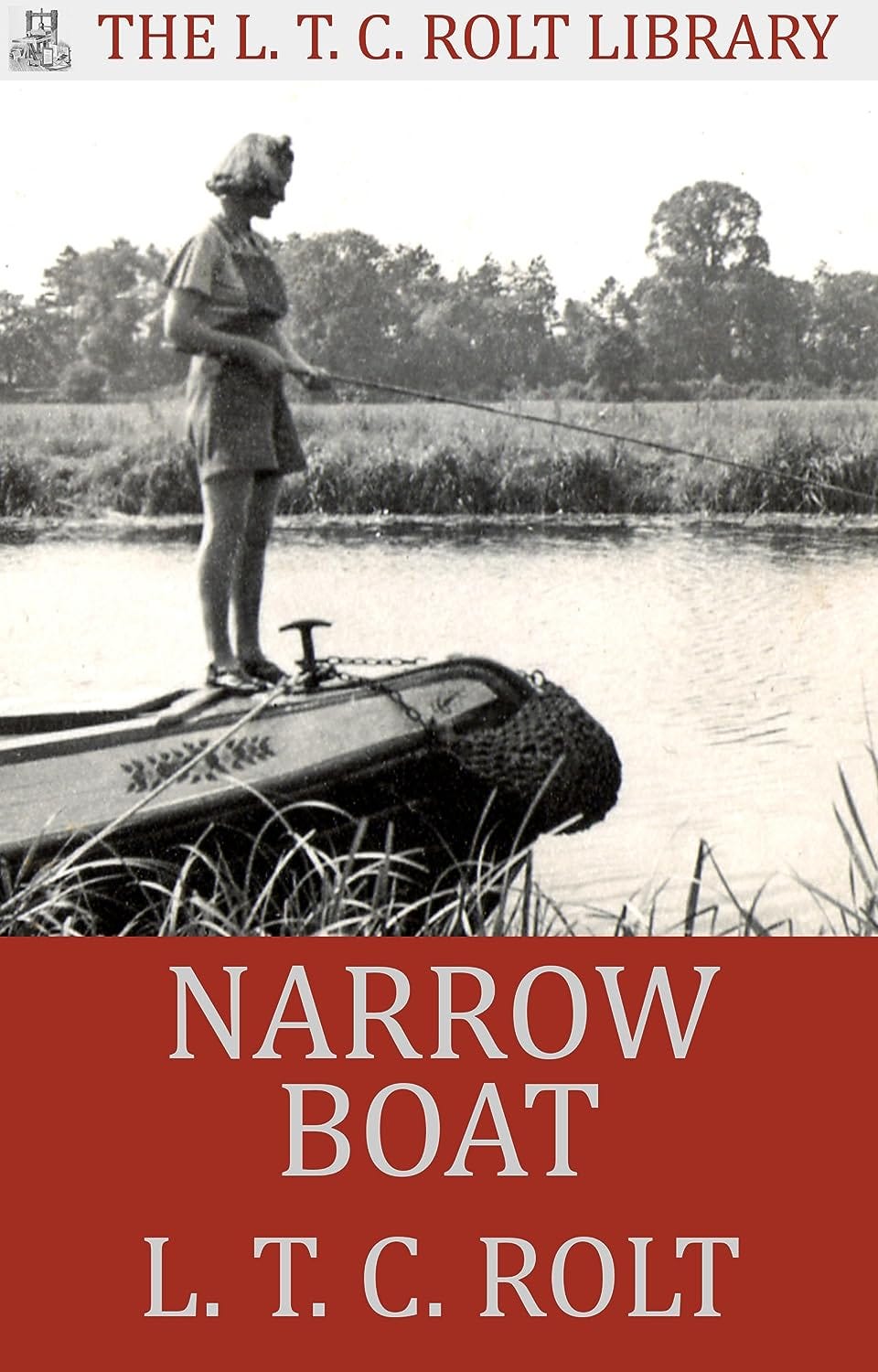

Before achieving some renown as a writer of fiction, Aickman was known for his crucial role in the preservation and restoration of Britain’s canal system: in ‘46 he created the Inland Waterways Association with LTC Rolt, the author of Narrow Boat, the book that had first sparked in Aickman a passion for the waterways.

Aickman took the role of chairman for himself and under his energetic leadership the IWA was hugely successful; policy disagreements ended his friendship with Rolt, who was expelled from the organisation.

Politically RA was on the Right, and he later wrote that he’d conceived of the waterways campaign and lifestyle as a ‘redoubt’ within which he and his friends would resist socialism, conformism, vulgarity, the decline of standards, urban sprawl, and everything else they hated.

By the 60s Aickman felt his waterways work was done and he retired as IWA chairman to concentrate on writing fiction. There was a novel, The Late Breakfasters, inspired by his failed romance with Elizabeth Jane Howard, who‘d married Kingsley Amis. But Aickman’s best known for his 48 ‘strange stories’, supernatural tales where oddity and mystery are the common themes.

Aickman never much cared to explain the weird phenomena his protagonists encounter, and it’s in their presentation of the alien and the inexplicable that the stories’ modernism is to be found. Comparisons can be drawn with Lovecraft, although RA’s work is subtler and more enigmatic.

In ‘The Hospice’, for instance, a motorist gets lost in the English countryside and chances upon a curious establishment where reside listless, apparently amnesiac individuals (including an elegant woman who takes a shine to the protagonist, allowing Aickman to use his flare for eroticism). These people might be guests, patients, prisoners, or something else again. What is this place? Is it the afterlife—the underworld maybe? Needless to say, no definitive answer is forthcoming.

Patricia Highsmith

1921—95. Novelist, short story writer. ’Crime fiction’ is an inadequate description for Highsmith’s voluminous output (22 novels and many short stories)—hers is a sophisticated oeuvre that incorporates existentialist themes, most notably in 1969’s The Tremor of Forgery, which recalls Sartre and Camus.

Like Dostoevsky she was fascinated by human psychology, and in particular the species’ penchant for the transgressive and the perverse. Highsmith employed a spare, classically modernist prose style; her main innovation was in refusing to impose a conventional moralistic framework. For instance, her most famous antihero, serial murderer and conman Tom Ripley, evades punishment for his crimes, at least in the first novel to feature him. In the first film adaptation (‘60’s Plein soleil with Alain Delon), to Highsmith’s disgust, Ripley is apprehended at the end.

Big respecter of all three.