#29 From the Twitter archives, part 12C: Daily Modernist series, poets

Three major figures spanning over a century.

Isidore Ducasse

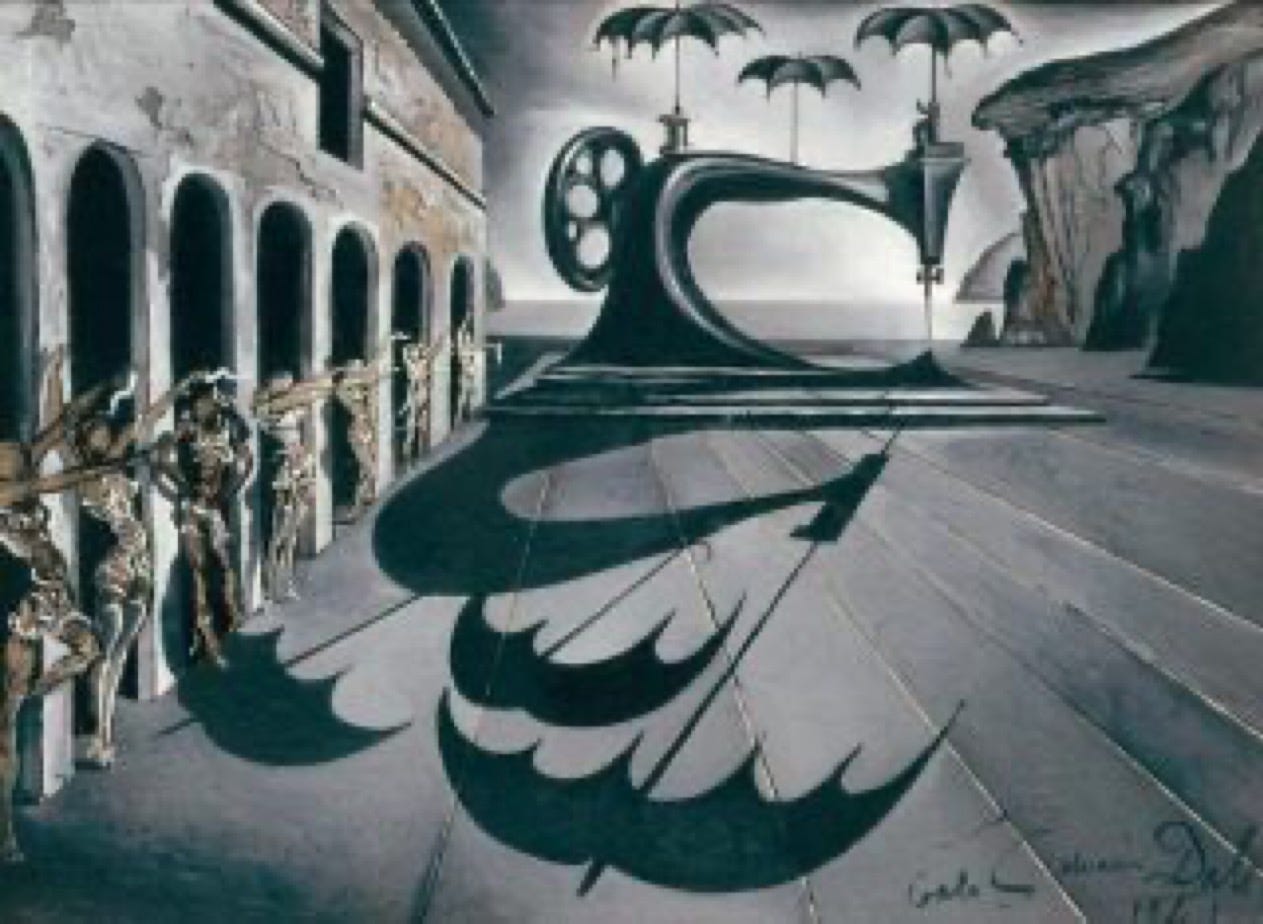

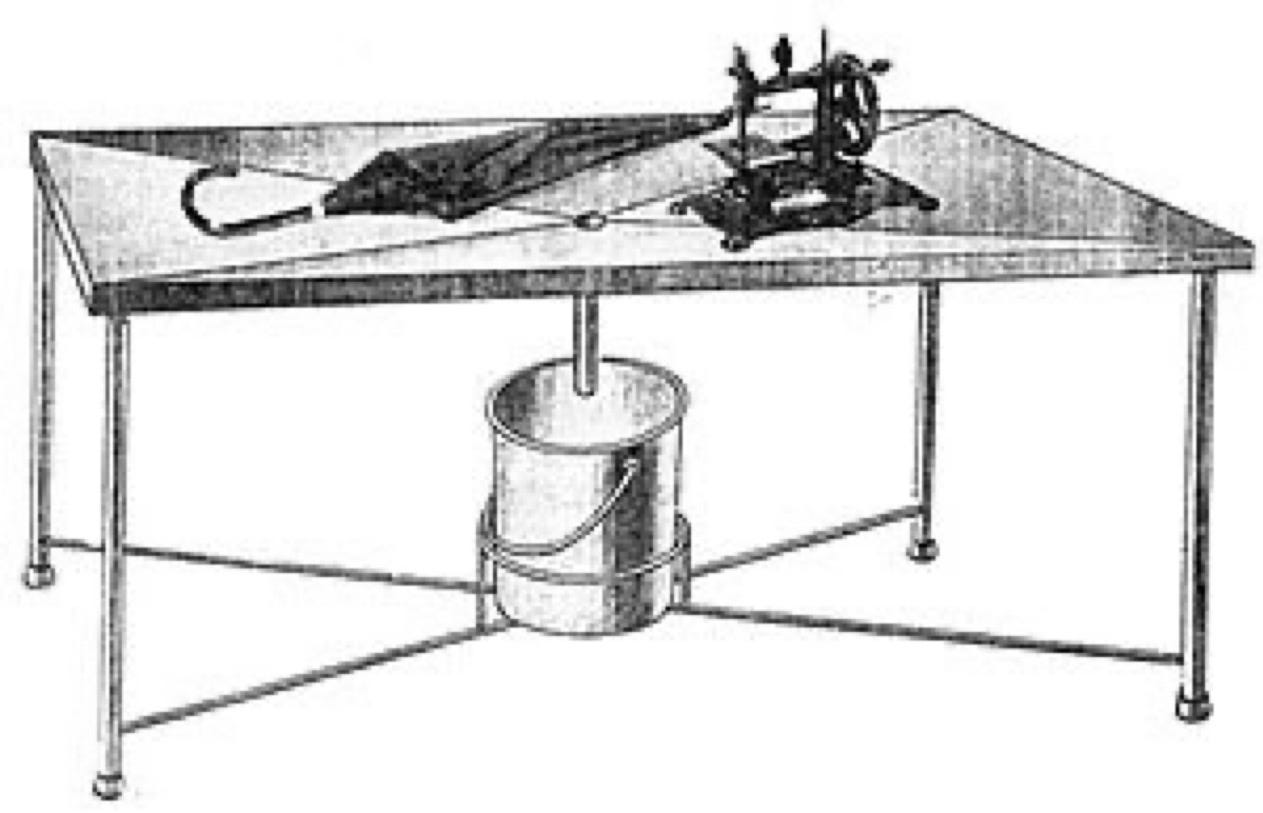

1846-70. Really a proto-modernist, the Uruguayan Ducasse was born in one capital city under siege (Montevideo) and died in another (Paris). A strange destiny for a still stranger young man, author of the most radical and perhaps most disturbing work in 19th-century literature—The Songs of Maldoror, penned under the name Comte de Lautréamont.

A bizarre, sarcastic celebration of wickedness, Maldoror went on to greatly influence the Surrealists. The book is fascinating for its acute grasp of what Baudrillard called ‘the eccentricity of evil’.

It’s difficult to say whether Ducasse was mad or just very skillful at inhabiting a mad persona—that of Lautréamont. In his follow-up, Poesies, he disavowed evil and pledged himself to the good—a sincere change of heart or merely a pragmatic move? As with so much about Ducasse we’ll never know.

One of his more famous utterances is found in the Poesies: “Poetry must be made by all, not by one.” Against the Romantic notion of lone, isolated genius, Ducasse seems to pit the idea of a poet who would draw upon the real experiences and stories of others. ”Hold to the common,” as Heraclitus says.

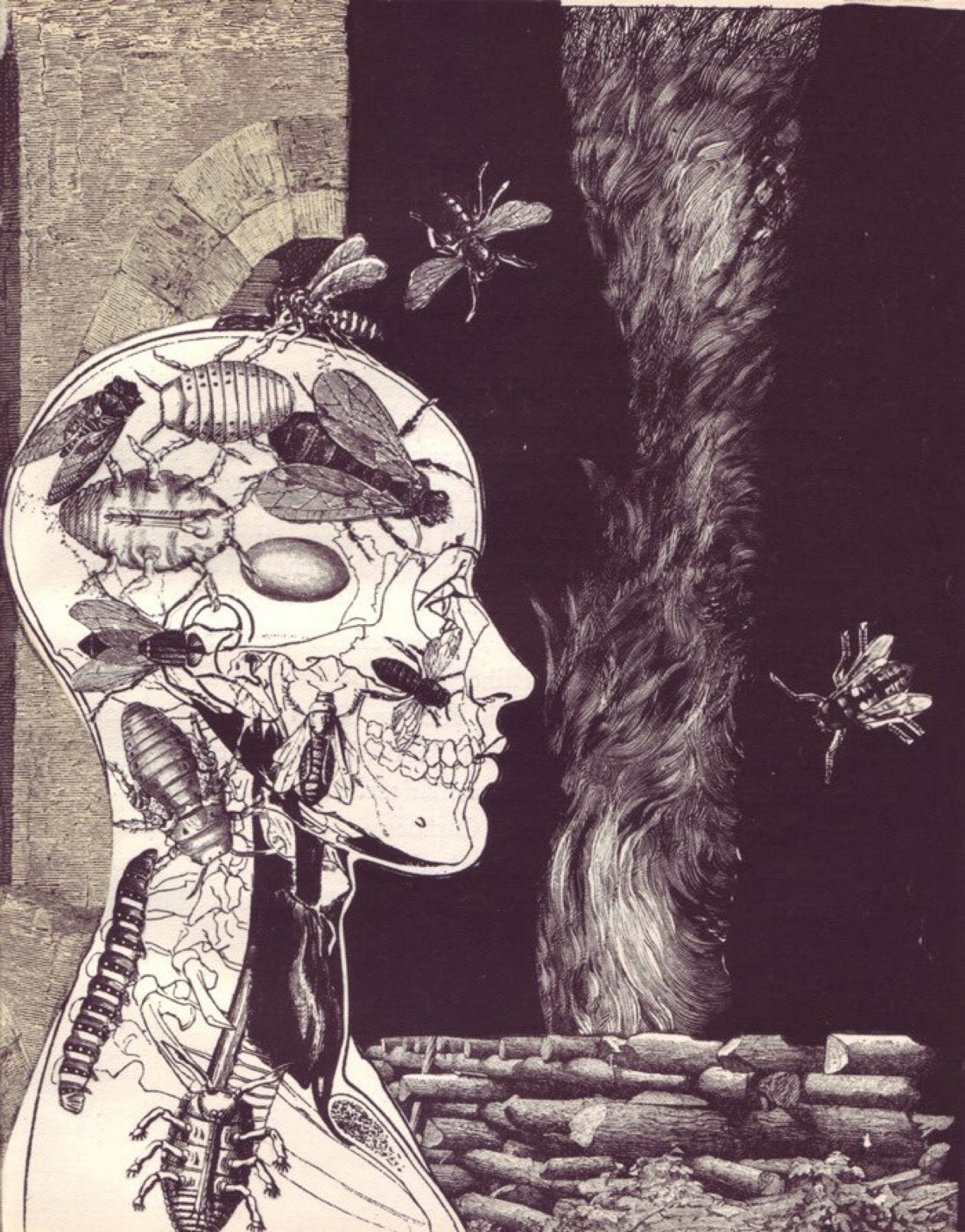

Georg Trakl

1887-1914. “Trakl’s poetry is for me a thing of sublime existence.” So said fellow Austrian Ludwig Wittgenstein, who anonymously provided the poet with a sizeable stipend so he could concentrate on writing. Trakl had trained as a pharmacist, and it was in a medical capacity that he served in the Austrian army during WW1, an experience he found unbearable.

Trakl’s poetry is dreamlike, often ominous, and possessed of a dark beauty uniquely its own. He’s considered one of the foremost German-language expressionists.

Below is one Trakl’s most celebrated poems, with Alexander Stillmark’s translation1 alongside.

Allusions in the poems suggest one source of Trakl’s anguish was his possibly incestuous relationship with his sister, the pianist Grete Trakl (1891-1917). Georg Trakl committed suicide by cocaine overdose in a Kraków military hospital; Wittgenstein arrived too late to stop him.

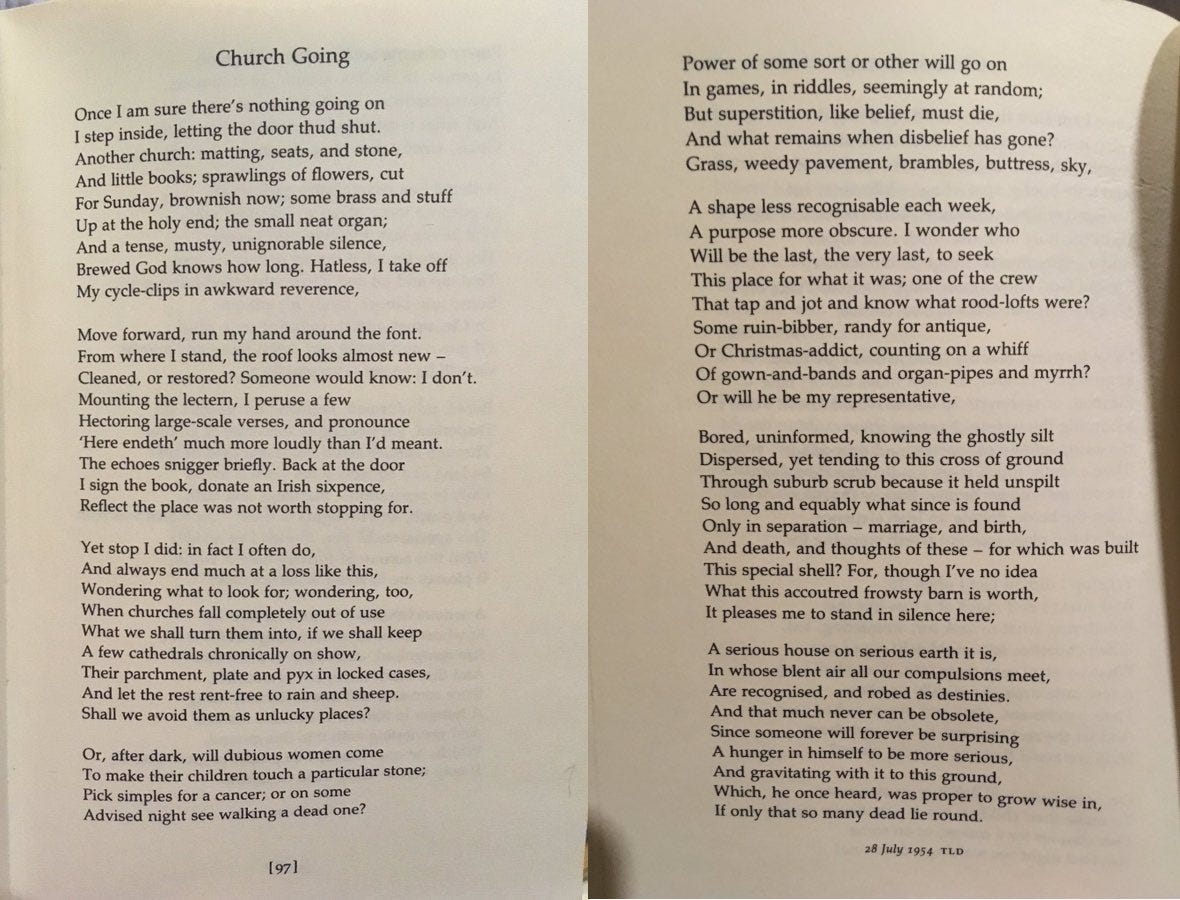

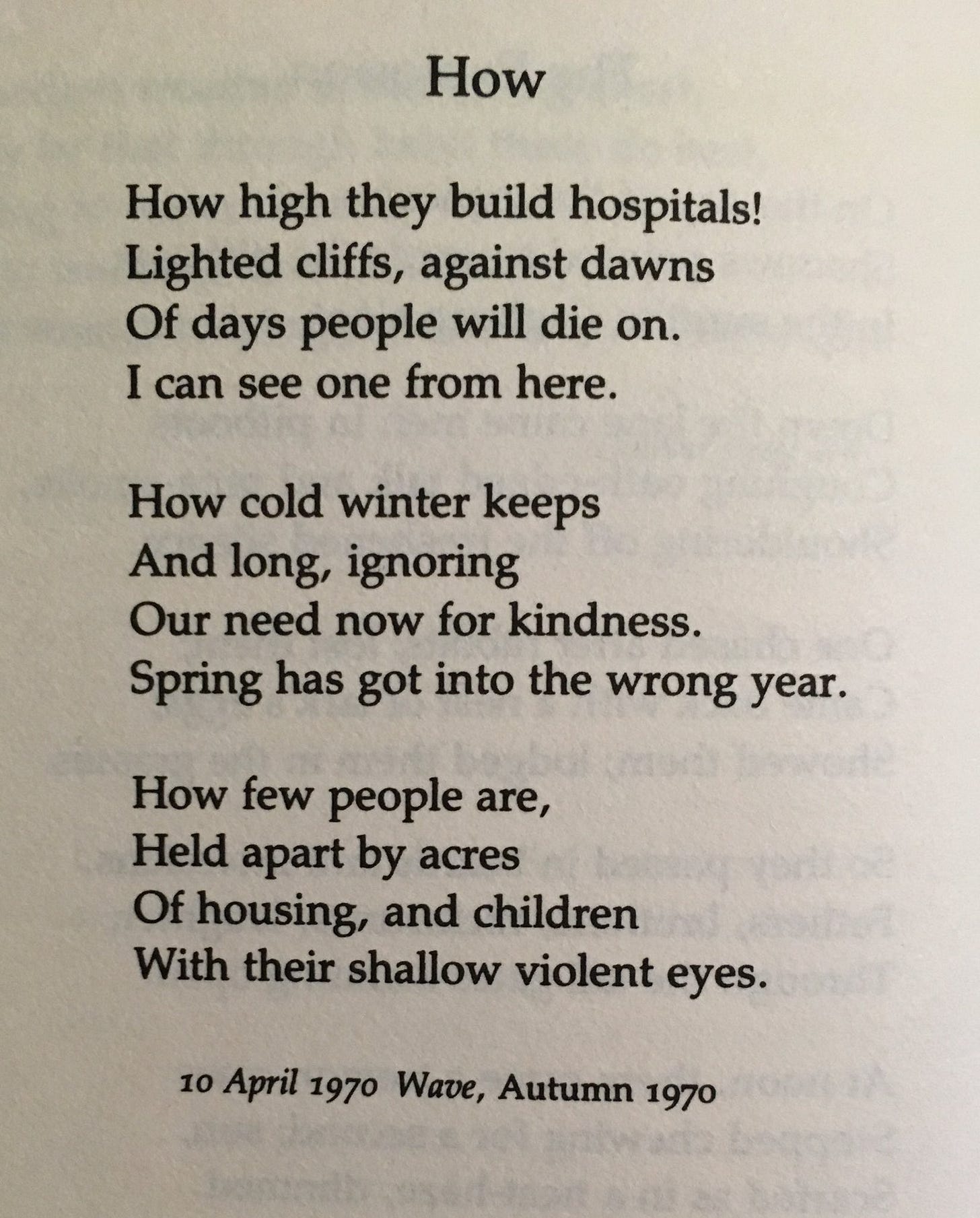

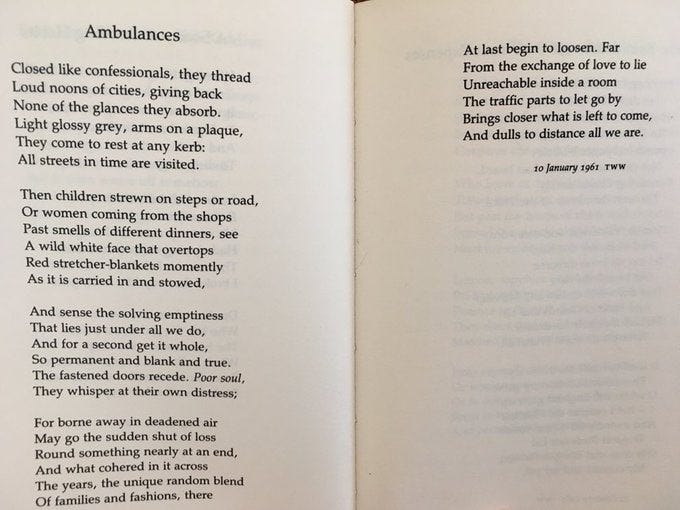

Philip Larkin

1922-85. Librarian (as well as a poet). Larkin would’ve likely objected to being included here, but critics did find modernist qualities in his works. The themes of the existentialists—alienation, absurdity, but also mystery—are very much present.

He once referred to himself, mockingly, as ‘a welfare state poet’. As a conservative he found Britain’s diminished postwar status lamentable, but no doubt also funny on some level. Irreligious, he accepted the collapse of religious belief. Though perhaps with a twinge of regret, as suggested by one of his most famous poems, reproduced below.

Larkin is simplistically pigeonholed by many as a doom and gloom poet, yet there’s also an abundance of wit in his works, and in many poems one encounters an unsettling haunting quality that goes beyond mere melancholy. Philip Larkin spent his working life as a librarian in Hull, a fittingly provincial town-one of his main themes was disappointment and the scaling-back of ambitions and expectations that often follows.

Although he never married, he enjoyed (or perhaps endured) a number of relationships with women. In 1984 he was offered the post of Poet Laureate—he declined it, feeling that the relative paucity of his output since the mid 70s disqualified him.

Georg Trakl Poems & Prose, translated by Alexander Stillmark; Libris, 2001.